posts

I’m grateful for Ben Myers’ new little book The Apostles' Creed: A Guide to the Ancient Catechism. This is the first title in Lexham’s Christian Essential Series that will include works on the Lord’s Prayer, Ten Commandments, baptism, the Lord’s Supper and others. Though Myers’ book is a bit more brief, it does resemble the aims of Michael Bird’s What Christians Ought to Believe (2016). These books evidence an encouraging trend that the contemporary church is seeking wisdom for faith and practice from the ancient church. May they be widely read and deeply digested. Though Myers’ book is just 133 pages and quite readable in one sitting, I chose to read it slowly (usually after morning devotions and prayers) following the book’s structure: 22 chapters organized by the three major articles on Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. I think this book would best be read over 22 days of devotions or 22 weeks as a small group Bible study or Sunday School class for adults and youth alike. It would also be a great resource for discipleship with a new believer. Breaking down each line of the creed, Myers’ engages Scripture and also leans on the thought of church fathers such as Ireneaus, Origen, Gregory of Nyssa, and Augustine. We grasp how the creed was articulated in the face of challenges from Gnosticism, Marcionism, Novatianism, and others. I think what I appreciated most was Myer’s ability to discuss the ancient creed with 21st century cultural concerns in mind: individualism, gender identity, and the material world. Myers’ presentation of the creed—and the gospel—was winsome, dogmatic, and relevant. Connecting with Secular Muslims through History and Film: Evaluating “Augustine: Son of Her Tears.”3/21/2018

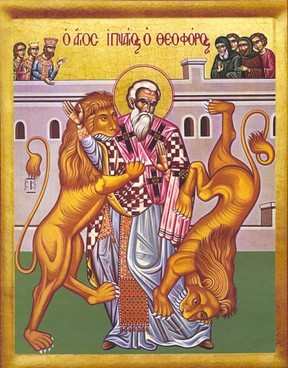

I'm looking forward to giving this paper at the Evangelical Missiological Society regional meetings in Raleigh, NC and Toronto over the next couple of weeks. My abstract follows: North Africa possesses a rich Christian history, including the stories of martyrs such as Perpetua and Felicitas (d. 202) and theologians like Tertullian (ca. 160-ca. 220), Cyprian (195-258), and Augustine (354-430). While many North Africans today may know these names, they do not know their faith stories. Is it possible to share the Christian message with a people through their own history? What if a high-quality feature film was developed that captured that story? This is the vision of a group of Middle Eastern and North African Christians who created “Augustine: Son of Her Tears,” which has recently been released and is currently premiering at film festivals and special showings around the Arab world (see trailer). In this paper, I discuss how the film is connecting with audiences, particularly North African secular Muslims. Following a brief background on the making of the film, a brief synopsis of it, and the initial distribution of the film, I discuss why Augustine’s story is meaningful to secular North Africans and what missiological lessons might be learned.  Originally given at the 2016 Evangelical Theological Society annual meeting, my paper, "Ignatius of Antioch's Trinitarian Foundation for Church Unity and Obeying Spiritual Leaders," has now been published in the Winter 2018 edition of Fides et Humilitas. In the abstract I write: While on the road to stand trial and face martyrdom in Rome, Bishop Ignatius of Antioch (d. ca. 110) authored seven letters—five to Asian churches, one to Bishop Polycarp of Smyrna, and one to the church at Rome. Providing rich insight into the issues of the second-century church in Asia, the letters also reveal a good bit of Ignatius’ theology, including his thoughts on ecclesiology, martyrdom, Judaism, heresy, and the Trinity. In this paper, I suggest that Ignatius’ pleas for church unity and obedience to the bishop—arguably the strongest themes in his letters—were founded on his understanding of the Trinity and that his ecclesiology depended on this developing Trinitarian thought. Read the complete paper HERE.  Scripture as Real Presence: Sacramental Exegesis in the Early Church. By Hans Boersma. Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2017, xix + 316 pp., $39.99, hardcover. [originally published in JETS 60:4 (2017)]. Scripture as Real Presence is the most recent book from prolific author and Regent College theology professor, Hans Boersma. A Reformed theologian, Boersma has also authored other works on sacramental theology, including Sacramental Preaching (2016), The Oxford Handbook of Sacramental Theology (edited with Matthew Leavering, 2015), Embodiment and Virtue in Gregory of Nyssa (2015), and Nouvelle Theologie and Sacramental Ontology (2013) among others. While building on these previous works, Boersma’s book also resembles the general aims of at least three other recent works: (1) Matthew Leavering’s Participatory Biblical Exegesis (2008), which navigates theological and historical interpretation of Scripture; (2) Andrew Louth’s Discerning the Mystery (2007), an apologetic for modern allegorical reading of Scripture; and (3) Frances Young’s Biblical Exegesis and the Formation of Christian Culture (1997), which aims to refresh the categories of patristic exegesis. Continuing the legacy of twentieth century scholars Henri de Lubac and Jean Daniélou, Boersma’s stated aim is one of ressourcement (p. 273)—to present and evaluate the sacramental reading of Scripture celebrated by the church fathers. Pushing back against modern historical approaches in biblical studies, Boersma defends this spiritual, theological interpretation of Scripture, which he defines as “simply a reading of Scripture as Scripture, that is to say, as the book of the church that is meant as a sacramental guide on the journey of salvation” (p. xii). In an introductory first chapter, the author attempts to guide the reader into hearts and minds of the church fathers, presenting their questions and concerns about Scripture. Instead of situating the Bible in Christian worship as Word and Sacrament, Boersma prefers to present the Word as Sacrament. Though human authors conveyed the words of Scripture, the Bible is a divine book that should be read in light of the divine economy. It should be read in light of Christ and the rule of faith. It should be interpreted for “a certain purpose, a particular aim—eternal life in the Triune God” (p. 159). In the chapters that follow (chaps. 2-10), the author discusses nine aspects or values for early Christian sacramental reading of Scripture. In chapter 2 (“Literal Reading”), Boersma shows that while fathers such as Gregory of Nyssa and Augustine valued a surface reading of Scripture, their understanding of literal is quite different than how we conceive of it today. By reading Genesis 18 (Abraham’s three visitors at the Oak of Mamre) through the eyes of Origen and Chrysostom, Boersma argues in chapter 3 for a “hospitable reading” of Scripture. He writes, “Reading Scripture is like hosting a divine visitor . . . when we interpret the Scriptures, we are in the position of Abraham: we are called to show hospitality to God as he graciously comes to us through the pages of the Bible” (p. 56). In chapter 4 (“Other Reading”), the author offers a basic presentation of allegory, affirming scholarly consensus which no longer holds to a strict dichotomony between Alexandrian and Antiochene schools of interpretation. In chapter 5 (“Incarnational Reading”), using the case study of Origen’s homilies on Joshua, Boersma argues that the church fathers saw the incarnation applied not only in the person of Christ and in the written Word of God but also in the life of the church. Chapter 6 (“Harmonious Reading”) explores how the fathers thought about the essence of music and how the Psalms brought healing, harmony, and unity to the body of Christ. In chapter 7 (“Doctrinal Reading”), Boersma discusses how the fathers understood Wisdom (Prov 8:22-25) and combatted an Arian reading of this text through a sacramental approach. In chapter 8 (“Nuptial Reading), he argues that Song of Songs was largely interpreted sacramentally (pertaining to the church and the soul) in the patristic period. In chapter 9 (“Prophetic Reading”), Boersma presents the fathers’ Christological readings on the Servant Songs of Isaiah, asserting that prophecy for the early church was “not only a fore-telling of future events” but a “forth-telling of present realities” (p. 247). Finally, in chapter 10 (“Beatific Reading”), the only portion of the book where the New Testament is emphasized, Boersma summarizes the fathers’ spiritual reading of the Sermon on the Mount. The purpose of the beatitudes is to “participate in [the] happiness of God” (p. 272). This book has a number of strengths. First, Boersma does a very thorough job of engaging the primary sources. Though he does not exhaust the corpus of patristic writings, his chosen case studies are strong and representative enough to make a compelling argument. Second, and related, the author succeeds in helping the modern theology student enter into the thought and church world of the fathers. By sketching out background details on subjects like philosophy and music, the reader is able to put on the lenses of Origen, Gregory of Nyssa, Augustine, and others and begin a sympathetic reading of the fathers. In terms of ressourcement, Boersma makes a winsome case for reading Scripture today in a sacramental manner. I only have two quibbles that are not content related. In terms of overall flow and structure, the book lacked cohesiveness between chapters. Church fathers, other scholars, and ideas are introduced again and again as if we had not read the preceding chapters. Because much of this book had already been published in other forms, more effort could have been made to bring this work together into one organic whole. Second, at points, the author seems unnecessarily critical of contemporary Reformed Protestants for failing to grasp patristic readings of Scripture. While his presentation of patristic sacramental exegesis was winsome, his invitation for modern Protestants to participate in this approach to reading the fathers and Scripture could have also been more welcoming. In sum, Boersma’s book is accessible and thorough and would serve as a good resource for a seminary level course on patristic exegesis, which is apparently where the book was in part nurtured and developed. Most of my reading in 2017 included academic books in history, theology, and missiology, and some practical devotional works. For some books, I wrote formal reviews for journals; for others, I simply read for my own enjoyment and edification. Some were published in 2017, while others were just new to me. So here goes:

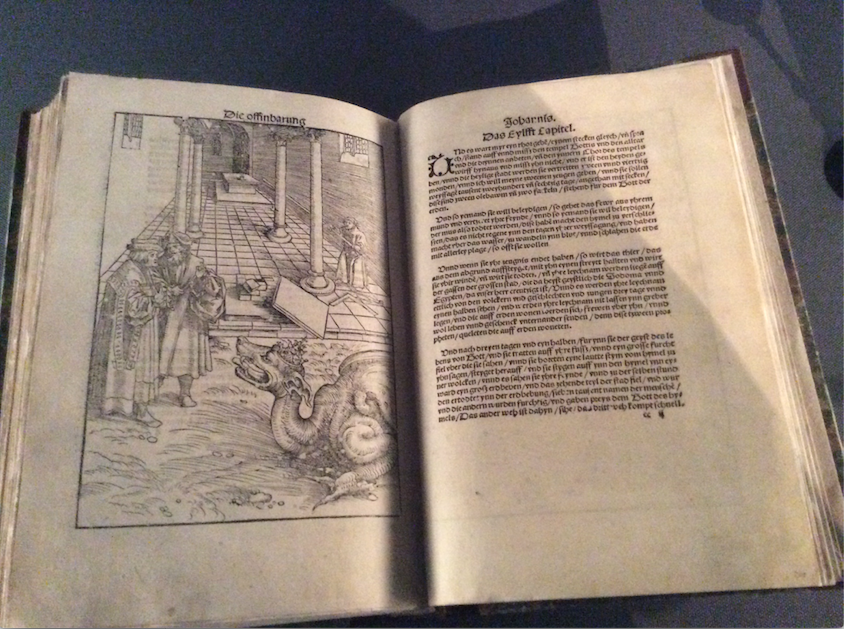

The Mission of the Church (Craig Ott, ed.). A timely book on an often-debated issue, Ott invited an excellent team of diverse scholars (Catholic, Orthodox, Mainline Protestant, Evangelical) to weigh in on the meaning of Christian mission. This book is a wonderful mix of agreement and diverging views on this important question. My full review HERE. Created and Creating: A Biblical Theology of Culture (William Edgar). Making a case for Christian cultural engagement, Edgar argues that “the cultural mandate, declared at the dawn of human history, and reiterated throughout the different episodes of redemptive history, culminating in Jesus’ Great Commission, is the central calling for humanity” (p. 233). This biblical theology of culture ought to shape how we think about work, government, the arts, and loving our neighbors. See my full review HERE. Scripture as Real Presence: Sacramental Exegesis in the Early Church (Hans Boersma). Continuing the legacy of twentieth century scholars Henri de Lubac and Jean Daniélou, Boersma’s stated aim is one of ressourcement (p. 273)—to present and evaluate the sacramental reading of Scripture celebrated by the church fathers. Pushing back against modern historical approaches in biblical studies, Boersma defends this spiritual, theological interpretation of Scripture, which he defines as “simply a reading of Scripture as Scripture, that is to say, as the book of the church that is meant as a sacramental guide on the journey of salvation” (p. xii). My review is forthcoming in JETS. Crossing Cultural Frontiers: Studies in the History of World Christianity (Andrew Walls). This is Walls' third "best of" compilation from previously published articles and chapters on world Christianity. Grouped into sections on theology of mission, Africa, and mission from the West, Walls’ continues to develop his lifelong exploration of indigenous Christianity—the gospel at home in every culture. My reviewing is forthcoming in Themelios. Abraham Kuyper: A Short Personal Introduction (Richard Mouw). In this short book, Mouw helps the reader meet Abraham Kuyper (1837-1920), the Dutch minister, newspaper editor, theology professor, university founder, and political party founder, who went on to become prime minister of the Netherlands. Believing that every aspect of our lives should be lived coram Deo (before God's face), Kuyper asserted that God should be glorified in business, the arts, politics, and education. Kuyper’s theology of work flowed from the “cultural mandate” of Gen 1:28 (“be fruitful and fill the earth”), which implied that humans labored to cultivate or make culture and to flourish in the process. Every Waking Hour (Benjamin Quinn and Walter Strickland). Defining work as “what creatures do with God’s creation,” the authors argue that since creation is inherently good, then work is good (p. 6). They define vocation or calling as “the way we make ourselves useful to others” (p. 8). Building on Jesus’ Great Commandment to love God and love others (Matt 22:37-39), they add that the purpose of vocation is to glorify God and serve others. Through pursuing vocation, humans act as image bearers doing God’s work. I've adopted this for a first year course on calling and vocation at CIU. Saved by Faith and Hospitality (Joshua Jipp). Jipp's work is a thorough study of hospitality in the New Testament, especially in Luke-Acts, John's Gospel, and in Paul's writings. Jipp summarizes, "If this work makes one point it is simply that hospitality to strangers--both understood as extending hospitality as host and receiving it as guest--is indeed at the heart of the Christian faith" (p. xii). Beyond his scholarship, Jipp shares practical suggestions for what that looks like in our communities while illustrating it from his own personal ministry. The Tech-Wise Family: Everyday Steps for Putting Technology in its Proper Place (Andy Crouch). As parents of kids with screens, my wife and I read this for practical help. More than advice on security settings or policing screen time, this book reminds us that the family is a community for cultivating wisdom and virtue. One of the best practical take aways (that we are still working on) is making the central living space in our home an increasingly tech free zone where we create (i.e. playing music and games, reading) instead of consume. Liturgy of the Ordinary: Sacred Practices in Everyday Life (Tish Harrison Warren). For me this was a purposefully slow read after morning devotions in summer, including a few days on a cabin porch in the Tennessee mountains. As the title suggests, following the church calendar of ordinary time, it is a call to orient our daily rhythms (even the mundane) along the sacred tracks of worship. This is well written, funny, and honest. The Songs of Jesus: A year of Daily Devotions in the Psalms (Tim and Kathy Keller). For most of the year, my wife and I read and prayed through this as part of our morning devotions. While this time has become oxygen for my soul, reading the Psalms and gaining insights on them from the Kellers helped shape our daily rhythms. In 2018, we're going to give God's Wisdom for Navigating Life (on Proverbs) a shot. You are what you read and this is what I am becoming. Merry Christmas.  Created and Creating: A Biblical Theology of Culture. By William Edgar. Downers Grove: IVP Academic, 2017. x + 262 pp., $24.00 paper. [note: this review was originally published in the Journal of the Evangelical Theological Society 60:3 (2017): 607-609]. Created and Creating is a new work from William Edgar, professor of apologetics at Westminster Theological Seminary (Philadelphia). Edgar’s previous books include A Transforming Vision: The Lord’s Prayer as a Lens for Life, Schaeffer on the Christian Life, and Truth in all Its Glory: Commending the Reformed Faith. Making a case for Christian cultural engagement, Edgar’s stated thesis is that “the cultural mandate, declared at the dawn of human history, and reiterated throughout the different episodes of redemptive history, culminating in Jesus’ Great Commission, is the central calling for humanity” (p. 233). With this focus, Edgar’s project bears resemblance to some other recent works including: 1) Andy Crouch’s Culture Making (2008), which invites Christians to be constructive contributors to culture; 2) Rod Dreher’s new work, The Benedict Option (2017) that actually urges believers to disengage from politics and to take shelter from the secular world; 3) Richard Niebuhr’s older theological work, Christ and Culture (1951) that discusses the various angles in which Christ relates to a given culture. Cultural engagement has also been a key theme in James K.A. Smith’s works, including his recent book, You are What You Love (2016). What makes Edgar’s work distinct is his primary emphasis on a biblical theology of culture. In the first of three parts (“parameters of culture”, chaps. 1-2) Edgar surveys nineteenth and twentieth century scholarship, showing the development of cultural studies in general. Next, he summarizes the thought of key twentieth-century theologians (including Lewis, Kuyper, Schaeffer, Conn) who have written about culture from a biblical perspective. In part 2 (“challenges from Scripture,” chaps. 3-7), the author carefully works through Scripture to explore the tension between not being conformed to the world (contra mundum), while also being a winsome participant in and shaper of culture. Finally, in part 3 (“the cultural mandate,” chaps. 8-12), Edgar fleshes out his thesis to show the cultural mandate at work throughout biblical redemptive history from the garden of Eden to the eternal state. There are many things to commend about this work but I will focus on three areas. First, since the author grew up in France and later served as a missionary there, he demonstrates a good grasp of the products of western culture (e.g., art, music), which he draws freely upon to make illustrations in the book. Also, particularly in the first section, he emulates his mentor Francis Schaeffer in being able to understand European philosophy and converse with these ideas from a biblical perspective. Second, Edgar succeeds in accomplishing his aims of presenting a biblical theology of culture by doing excellent exegetical work throughout the book. His study is rich with reflection on particular passages, including biblical terms and themes, all within the context of biblical redemptive history. This thorough and sober study of Scripture might provide the best response to date to the claims of cultural disengagement laid out in Dreher’s Benedict Option even though that is not Edgar’s specific aim. Finally, the author’s discussion on the image of God in man certainly critiques the historic social sins of slavery and racism though, again, that is not his deliberate purpose. A final strength was Edgar’s discussion in chapter 12 on “culture in the afterlife.” Most reflections on Christian cultural engagement focus on the here and now; so it was thought provoking and even inspiring to think about culture making in heaven. Edgar accomplishes the goals of his study by exploring the cultural mandate even in the eternal state. To these affirmations, I add three areas of constructive critique. First, though Edgar deeply engages Scripture and western philosophy, the Christian voices that inform much of his thought are almost entirely white, western, male, and Reformed. While no disrespect is meant for the likes of Murray, Kuyper, Vos, Frame, Conn, Schaeffer, Keller, and others, if Edgar had engaged other diverse global theological voices, then his book would have been strengthened. Second, I was hoping that the third part of the book would do more to unpack a theology of work. Although the title of chapter 8 (“first vocation”) hints at such a discussion, and a paragraph in chapter 12 (p. 218) only briefly raises the issue of work, this reader would have appreciated more biblical and theological reflection on vocation. Finally, in chapter 12, Edgar’s assessment of Augustine’s thought on cultural engagement from City of God appears incomplete. Edgar writes: “Yet [Augustine’s] dichotomy between the two cities, based on the two loves, leaves the reader to believe the present world is a confinement, a place of captivity, as we await immortality” (p. 221). While Augustine regarded believers as temporary pilgrims in the earthly city who yearn for the heavenly city, he also affirmed that actively living in the earthly city prepares the believer for heaven. Also, Augustine encouraged believers to actively participate in society in order to influence the earthly city with heavenly values. Augustine applied these values in his own ministry by serving as a monk-bishop and living in a monastery (in the bishop’s house) near Hippo’s center. There he and the brothers regularly open their doors to visitors and demonstrated hospitality. Further, under the Theodosian code, Augustine functioned as a judge and mediator in the Roman courts so he could influence local society with biblical values (cf. Augustine, On Christian Doctrine 1.4.4; Sermon 88.15; City of God 22.21.16; 21.15; Letter 133; Possidius, Life of Augustine 19). In summary, William Edgar has written a thoughtful introductory work on a biblical theology of culture. This would function as a good supplementary text to an Introduction to Mission or Biblical Theology of Mission course at the seminary level, especially if it is read alongside other works from diverse global theologians.  The Evangelical Missiological Society Compendium (EMS 25) was published last week. Churches on Mission: God's Grace Abounding to the Nations (EMS 25) captures some of the papers from the 2016 EMS national conference. I had the opportunity to write chapter 2 entitled, "When the Church was the Mission Organization." My chapter intro reads: Critical observers of mission history remark that following the sixteenth-century Reformation in Europe, one reason for the initial inaction of Reformed Protestants in global mission was the lack of missionary sending structures. Roman Catholics on the other hand possessed a number of sending structures—most notably monastic orders (e.g., Franciscans, Augustinians, Dominicans, Cistercians, and Jesuits) that were formed in the medieval period for the purpose of sending witnesses to the world. So how did mission sending happen and what structures were in place in the early and medieval church prior to the rise of monastic missionary orders? In this article, I argue that the church itself was the key organism and catalyst for mission sending. In doing so, I offer an alternative conclusion to Ralph Winter’s (Winter 1999, 220-229) popularly accepted claim that there were two structures of redemption in mission history—modalities (e.g., churches) and sodalities (e.g., monastic movements)—and argue that the church was the sole means of sending. To make the case, I will highlight the examples of five missionary-monk-bishops who served between the fourth and eighth centuries: Basil of Caesarea (fourth-century Asia Minor), Patrick (fifth-century Ireland), Augustine of Canterbury (sixth- and seventh-century England), Alopen (seventh-century China), and Boniface (eighth-century Germany). Though not exhaustive, these cases serve as representative models for early Christian and medieval Christian practice in the global church.  In late 1521 and early 1522, a young scholar and theology professor risked his life to translate the New Testament into colloquial German. Convinced that the Word of God had final authority in a believer’s life and that every Christian possessed the ability to understand Scripture even without the aid of a priest or teacher, Martin Luther (1483-1546) modeled very practically the value of sola scriptura through this translation exercise. Although Luther and other early Protestant reformers were not directly involved in cross-cultural, global mission, the principle of sola scriptura that they championed provided a theological foundation and fresh vision for Bible translation that invigorated the missionary enterprise. In this paper, I will argue that the value of sola scriptura was the Reformation’s greatest contribution to Protestant global mission and that the recovery of vernacular Bible translation as a central mission practice contributed to making the modern missions movement revolutionary. Following some preliminary thoughts on the vernacular principle and sola scriptura, I will sketch out the work of key missionary Bible translators from the 17th to the 20th century to show that Protestant mission has indeed been a mission of translation. I will conclude with some remarks on how sola scriptura and the vernacular principle have shaped evangelical Protestant and how they might offer guidance moving forward in 21st century mission. note: This is the abstract from a paper I'll be giving at the "Legacy of the Reformation" conference at Liberty University. The picture above is an early print of Luther's German NT, which I photographed at the Luther museum in the Wartburg castle in Eisenach, Germany.  Alan Kreider. The Patient Ferment of the Early Church: The Improbable Rise of Christianity in the Roman Empire. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2016. Pp. xiii+321. ISBN 9780801048494. $26.99 This new work is the latest from Alan Kreider (1941-2017), professor emeritus of church history and mission at Anabaptist Mennonite Biblical Seminary (note: Prof. Kreider passed away in the Spring of 2017. May he rest in peace). The Patient Ferment certainly resembles Kreider’s previous books on the emergence of Christendom in the early church and Roman Empire, including The Origins of Christendom in the Christian West (2001), The Change of Conversion and Origin of Christendom (2007), and Worship and Mission After Christendom (2011). Other related works include Ramsey MacMullen’s Christianizing the Roman Empire (1984) and Andrew McGowan’s Ancient Christian Worship (2014). As the title indicates, Kreider’s central thesis is that the Christian faith—an otherwise superstitio from insignificant Palestine—captured the hearts and minds of Roman pagans because of the transformed habitus of Christian believers. This patient witness that grew over time, particularly in the first three centuries, proved to be attractive to the Romans. In parts 1 and 2 of the book, Kreider argues for this patient growth of the church in pagan Rome, while in part 3, he discusses the means through which the Christian habitus was formed—particularly catechesis and worship. Finally, in part 4, in good Anabaptist fashion, he claims that this patient ferment began to be lost with the emergence of the Emperor Constantine and through the influence of the church father Augustine of Hippo. There is much to like about this book. In typical Kreider fashion, he thoroughly engages ancient texts and the best current scholarship to advance his thesis that Christianity conquered the hearts of many Romans prior to the rise of Constantine through a patient witness. Certainly, his Anabaptist lenses on early Christian history—especially regarding the aversion to killing and the lack of political power possessed by Christians—come to bear in this work. I also find it refreshing that Kreider looks at the early church and its thinkers from a missiological perspective, which is certainly uncommon in patristic studies. While Kreider’s chapters on forming the habitus (on catechesis and worship) are not terribly groundbreaking, he does do a good job of situating early Roman church worship—practices such as the sharing of meals and liturgy—within the context of the Roman world. In that sense, he is a faithful guide to show how the Jesus movement of the eastern Mediterranean world became Roman Christianity. Finally, Kreider does a good job of evaluating the conversion of Constantine against the grid of third- and fourth-century initiation (evangelism, catechesis, baptism) and he successfully argues that Constantine was not regarded by the church as a believer until his baptism at the end of his life. Given these strengths, I do have a couple of constructive critiques. First, while Kreider’s central argument that the Christian habitus—the visible way of life among pagans—was the main strategy for early Christian mission, he seems to downplay the place of gospel proclamation in mission. Without a doubt, Christians witnessed through their daily character in the marketplace and public square as religious minorities. However, though a religio illicita, Christianity was still very much a public religion in Rome and there is good evidence that open proclamation took place on interpersonal levels but also through the work of itinerant evangelists as the author of the Didache, Origen, Eusebius have reported. Also, the pre-Constantinian ministries of Gregory Thaumaturgus, Gregory the Enlightener, and arguably Irenaeus of Lyons point to the work of ministers engaged in evangelistic proclamation. So while I affirm his claims of the Christian habitus being key to a patient witness, I think more space could have been given to the place of proclamation in early Christian mission. Second, in the final chapter, Kreider asserts that through allowing and even affirming state intervention into religious disputes (with Donatists and Pelagians), Augustine set into play a “missional revolution” in which “the carriers brought a gospel in which impatient, forceful actions—animated of course by loving intentions—replaced patient actions” (p. 294). This element of Kreider’s argument was quite brief and rather unconvincing and could have used much greater support in the way of argument and documentation. What is ironic to me is that Augustine’s engagement with the Donatists and Pelagius and those they influenced was a narrative marked by much patience that included much writing, traveling, and meeting to defend sound teaching. I would add that persuasion and teaching remained Augustine’s primary means of striving to reach these groups. In summary, I think that students and professors of early Christianity in the Roman Empire would benefit from this book. Also, given the book’s emphasis on witness through a patient Christian habitus, I think many pastors today would be challenged by it as they minister in a fast paced society and lead busy churches that are often packed with activity.  Gregory the Great: Ascetic, Pastor, and First Man of Rome is the most recent work from George Demacopoulos, professor of Orthodox Christian Studies at Fordham University. Having written his doctoral dissertation on Gregory and spiritual direction, Democopoulos’ other related works include Five Models of Spiritual Direction in the Early Church (2006) as well as an updated translation of Gregory’s Pastoral Rule (2007). In terms of related works from other scholars, while the author has offered his own helpful literature review (pp. 4-9), this work particularly resembles Robert Markus’ Gregory the Great and His World (1987), Carole Straw’s Gregory the Great: Perfection in Imperfection (1988), and Conrad Leyers’ Authority and Asceticism from Augustine to Gregory the Great (2000). At the outset of the book, Democopoulos clearly states his thesis: “that Gregory’s ascetic and pastoral theology both informed and structured his administration of the Roman Church” (p. 11) and the work is divided into three main sections. In the first part, Democopoulos aims to outline Gregory’s ascetic theology in general. In the second part, he seeks to show how ascetic thinking shaped his pastoral theology. Finally, in the third section, he advances the argument that Gregory’s ascetic theology also influenced his leadership of the church at Rome. It is the third area that is arguably the most ground breaking because Gregory is generally remembered as a strong administrator whose style resembled that of a governor more than that of a monastic abbot. Through his argument, Democopoulous attempts to synthesize the “two Gregorys” that have been portrayed by other scholars. In his characteristic thoroughness, Democopoulos interacts with much of the Gregorian corpus to present his case. There is much to appreciate about this study. In part one of the book (pp. 19-30), the author does a good job discussing the tension of the contemplative life and the active life that ministry-minded monks such as Basil, Augustine, and Gregory wrestled with and addressed. Democopoulos makes a good argument that Gregory probably had the most developed ideas about this among the fathers; that he had “an ascetic vision that emphasized service to others as the climax of the spiritual and ascetic life” (p. 26). That is, a monk should gladly have his contemplative experience of prayer, fasting, etc. interrupted in order to serve others. While I think Democopoulos has made a good point here, this advanced loving God/loving neighbor aspect of ascetic theology probably also informed Gregory’s passion for cross-cultural mission to the Lombards and especially to the Anglo-Saxons. Though the author dedicates chapter 13 of the book to these mission efforts, a monastic theology of service expressed in mission was absent. I think further reflection in this area of Gregory’s ministry would strengthen Demacopoulos’ overall “service as the climax” argument. I think Democopoulos also succeeds in part two of the book by showing Gregory’s integrated ascetic and pastoral theology. In particular, he argues that a key component of being a pastor was being a spiritual director (cf. pp. 53-56), which was strengthened by ascetic concerns. He builds his argument not only through a good treatment of Gregory’s Pastoral Rule but also by exploring parts of the Gregorian corpus that are not as overtly pastoral in focus, including his commentaries on Job and Ezekiel and his homilies on the Gospels. A final strength of the work is in part three—in which Democopoulos attempts to connect Gregory’s asceticism with his practical leadership of the Roman church—as the author presents Gregory’s regard for Peter. Unlike other Roman bishops, Gregory presents Peter as weak and fallible and it is this weakness that actually makes him a strong and model leader (pp. 153-155). While this character analysis of Peter toward the office of bishop certainly supports Democopolous’ acetic theology connection to leadership, I found the remainder of part three of the book a bit less convincing in making the connection between Gregory the monk and Gregory the strong, prefect-like leader of the church at Rome. In short, this is a profitable and useful study of the famous Roman bishop through the lenses of ascetic theology. While graduate students and scholars and students of early Christianity would benefit most from this book, it is written at such an accessible level that interested undergraduates and possibly pastors would profit from it as well. |

Archives

November 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed