posts

|

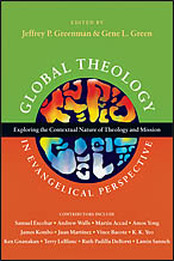

While traveling to Belgium and Scotland this week, I had some time to read through this excellent work and write up the following review. I am grateful to Adrianna Wright at Intervarsity Press for the review copy. Here goes: Global Theology In Evangelical Perspective: Exploring the Contextual Nature of Theology and Mission by Jeffrey P. Greenman and Gene L. Green, eds. Downers Grove: IL: Intervarsity Press, 2012. 267 pp. Paperback, $26.00 Global Theology is the volume that emerged from the April, 2011 Wheaton theology conference. Readers will be encouraged to know that Wheaton has archived many of the lectures given at the conference (which I had the privilege to attend) and they can be accessed HERE. Edited by Wheaton professors Jeffrey Greenman (theology and ethics) and Gene Green (New Testament), both of whom contributed a chapter to the book, Global Theology is a rich introductory volume that offers a voice to a number of key international and minority North American theologians. Built on the conviction that Scripture is authoritative and that all theology (even Western theology) is contextual, and the acknowledgement that the majority of Christians today are from the Global South, this is a timely and important work. In terms of its general aims, the work resembles Ott and Netland’s Globalizing Theology (2006), Tennent’s Theology in the Context of World Christianity (2007), and Parratt’s An Introduction to Third World Theologies (2004). Following a brief summary introduction by Green, Part One features three chapters: a historic “long view” of global Christianity and theology from Andrew Walls (chap. 1); a discussion of his well-known translation principle in missions history by Lamin Sanneh (chap. 2); and Green’s reflective chapter on the challenge of global hermeneutics (chap. 3). Part Two is dedicated to non-Western theologies and features theologians from Latin America (Samuel Escobar and Ruth Padilla-DeBorst, chaps. 4 and 5), China (K.K. Yeo, chap. 6), India (Ken Gnanakan, chap. 7), Africa (James Kombo, chap. 8), and the Arab World (Martin Accad, chap. 9). In Part Three, the reader hears from four minority North American theologians: Terry LeBlanc (chap. 10) presenting Native American theology; Juan Martinez (chap. 11) discussing Hispanic theology; Amos Yong (chap. 12) surveying Asian-American theology; and Vincent Bacote discussing African-American theology (chap. 13). In Part Four, some next steps perspectives are offered by two (white) North American theologians who seem to have Western evangelicals as their audience. Mark Labberton (chap. 14) urges global Christians to pursue humility and a love for God, the Scriptures, and neighbor in the process, while Jeffrey Greenman invites global Christians to recognize their need for the richness of a global theology (chap. 15). This book has a number of strengths. First, the Wheaton theology conference and book editors invited some of the finest theologians in the world to participate and have modeled a winsome, humble exercise in promoting global theologizing. When I saw the lineup for the conference, I happily traveled to Chicago at my own expense to hear these scholars, pastors, and missionaries. Now, English speaking students have the contents of the conference in one, affordable book. Second, this book serves as an excellent introduction to global theology. Each chapter, in 12 to 17 page bites, could be expanded into a book of its own and each author has offered a helpful short bibliography at the end that could easily become the syllabus for a course on theology in a given context. If Global Theology had been available this past January, I would have certainly assigned it as a required text in my global theology course—next time! Third, while on one hand Latin America seems overly represented, I think it is important that at least one female theologian (Padilla-DeBorst) was included. In his chapter, Escobar also did a good job of alerting readers to the work of other Latin American women theologians (p. 84). Finally, the work is framed by an important look at history (Walls and Sanneh) and closes with admonitions to humility from two North Americans (Labberton and Greenman) who have modeled in their chapters the humble posture that they are advocating. I have two critiques of the work as a whole. First, though Greenman acknowledges that there are no representatives of Western academic theology (p. 237), I think that the volume would have been more truly global if it had included an evangelical theologian who had worked through the realities of post-Christian, post-modern Europe. Though no one specifically comes to mind, I think a Scandinavian, French, Irish, or even Australian voice would have been appropriate—next time! Of course, though Western academic theology was not formally represented Green, Walls, Labberton, and Greenman are still theologians from the West who have certainly retained at least some of their theological Westernness. Second, and related, I think it would have been good if at least one of the editors was non-Western. While Green and Greenman have done fine work, I think such a move would have made the volume even more credible and effective. In this last section I want to engage with some specific issues raised in some of the individual chapters. While the scope and trajectory of the book is vast, I will limit my critique and discussion to points made in four chapters. First, Sanneh (chap. 2) argues that early Christianity “was defended more as a ‘Greek’ philosophy than as the way of Jesus” and “in the early missionary literature the reader is struck by the lack of local detail and color” (p. 41-42). It seems that Sanneh has in mind the Greek apologists (Justin, Athenagoras, Aristides); yet, I would argue that much color and insight into the life of the church can be gleaned from early Christian literature such as the Didache, the Epistle to Diognetus, and even Justin’s First Apology and Dialogue with Trypho. Also, Sanneh mistakenly identifies Cyprian of Carthage as a “Greek convert and theologian” (p. 44) when Cyprian was African and Latin-speaking, and his theology was hardly philosophical or speculative. Next, while Padilla-DeBorst has written a beautiful chapter (chap. 5), I do have a couple of quibbles. First, much of her material on the Latin American Theological Fellowship (formerly Fraternity) overlaps with Escobar’s presentation and it seems that the book as a whole would have benefited from some more editing of chapters 4 and 5. Second, in her conclusion (“composing songs of hope”) she seems to take particular aim at imposed theological constructs from North America, especially complementarianism (p. 100). While not all North Americans are complementarians, my question is how does she respond to other Latin American theologians who have come to the studied conclusion from Scripture that only men should occupy the office of pastor or elder? Third, In Yeo’s very stimulating chapter (chap. 6) on Christian Chinese theology in which he strongly asserts the authority of Scripture, he also looks to Confucian thought as the primary conversation partner in doing theology in the Chinese context. He writes, “our work . . . assumes the scriptures of the Confucian classics as the ideal text of Chinese culture” (p. 107). While I must admit my concern for syncretism—one that is alleviated largely by Yeo’s high view of Scripture—my bigger question is are the Confucian scriptures and accompanying worldview normative for all Chinese peoples? Are there Chinese Christians, including those from various cultural groups, for whom Confucius is not relevant? Finally, Yeo makes what I consider a troubling assertion: “[the] Confucian classics and the Bible are fairly close at certain points while differing radically from each other at others. Holding on to their incommensurability in tension is a challenging interpretative move of CCT that will fulfill each other’s blind spots” (pp. 114). Does Scripture have blind spots? Such a statement seems to contradict his previously stated evangelical convictions. Finally, Accad (chap. 9) asserts that Middle Eastern theology in a Muslim context ought to “move from a reactionary to a constructive theology” (p. 157). While I appreciate his peaceful and edifying spirit, especially in a part of the world where religious dialogue can be quite tense to say the least, I would simply assert that much of the theological development in the history of Christianity (i.e. the Apostles Creed, Nicene Creed, Augustine’s writings on grace) has often emerged in the context of defending the faith. The creeds in particular are certainly didactic (what should a Christian believe?) but also apologetic (what should a Christian believe in contrast to competing worldviews?). Eighth-century Arab theologians such as John of Damascus and the Nestorian bishop Timothy certainly advanced sound doctrine in an apologetic manner before a Muslim majority. In short, is there a way in the Middle East in which Christian thought and even a Christian apologetic can be presented in a winsome, loving, and constructive manner? I trust that these final critiques and questions contribute to the global theological reflection initiated by the authors of Global Theology. Indeed, our aim is to be a global hermeneutical community gathered around the authoritative Scriptures and led by the Holy Spirit seeking to do theology in the context of the real issues of our day. I am grateful for Global Theology and I trust that other readers will be as well. I arrived this morning in Brussels and then immediately trained over to Leuven for the International Donatist Studies Symposium--a conference on early African Christianity hosted by the Catholic University of Leuven. I'm privileged to be staying at a monastery run by the Augustinians of the Assumption order. The conference includes a lineup of some very impressive scholars from Europe, the USA, and Australia (see full schedule HERE). I'm especially looking forward to papers from Maureen Tilley (Fordham University), Jane Merdinger, and Geoffrey Dunn (Australian Catholic University)--scholars whose works I've greatly benefited from in my own research and teaching. I'm quite humbled to be here and truly wondering how I got invited in the first place:). While struggling to keep myself awake today, I got to walk around, have some food (and strong espresso) and, of course, could not help but observing Leuven daily life. The city center is beautiful and graced with some amazing cathedrals, there are several cobble stone walking streets with inviting shops, and many save on the price of gas by getting around on bicycles. I was reminded of the three years that Shawn and I lived in France and how much I appreciate Europe. I came across this short video of the city that you might enjoy. Peace! els On Thursday of this week, I'll be giving a paper at the University of Leuven in Belgium at the International Donatist Studies Symposium. Focusing on my two loves--mission and early Christianity--I will read a paper entitiled, "Augustine, missionary to heretics? An appraisal of Augustine's missional engagement with the Donatists."

Here's a glimpse of the paper from the abstract: Augustine is well remembered as a theologian, polemicist, and church leader, especially in his dealings with the Donatists. In this paper, my aim is to take an admittedly different approach and examine Augustine's Donatist interactions afresh in the light of Christian mission. That is, as Augustine regarded the schismatic group as a heretical mission field—distinguished not by cultural or geographical barriers but through ideology—he deemed that they were in need of conversion to the true church. In order to accomplish this, I will propose a working definition of Christian mission that stems from the Scriptures, which reflects the activity of the church. Second, I will briefly discuss Augustine's heretical branding of the Donatists, which made them a focus of mission. Finally, I will build the case for Augustine's missional engagement with the Donatists—even that which included the involvement of the state—by exploring his interactions with them over three periods between 392 and 419. From this narrative, an argument will be made for Augustine's understanding of and approach to Christian mission. You can read the rest of the paper HERE. Let me know your thoughts! els |

Archives

November 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed