posts

During a recent visit to Savannah, I was able to learn a bit more about George Liele (1750-1828), the first American Baptist missionary. In the Biographical Dictionary of Christian Missions, Alan Neely has helpfully written: Born a slave in Virginia, Liele was taken to Georgia, where he was converted in 1773 in the church of his master, Henry Sharp. He soon became concerned about the spiritual condition of his fellow slaves and began preaching to them. In 1775 he was ordained as a missionary to work among the black population in the Savannah area. Like many other slaves, he sided with the British in the Revolutionary War, as did his master, who set Liele free in 1778. In order to be evacuated with other royalists and British troops, Liele obtained a loan and accepted the status of indentured servant to pay the passage for himself, his wife, and his four children on a ship bound for Jamaica. Landing there in January 1783, he soon repaid the debt and secured permission to preach to the slaves on the island. Thus by the time William Carey—often mistakenly perceived to be the first Baptist missionary—sailed for India in 1793, Liele had worked as a missionary for a decade, supporting himself and his family by farming and by transporting goods with a wagon and team. Apparently, he never received or accepted remuneration for his ministry, most of which was directed to the slaves. He preached, baptized hundreds, and organized them into congregations governed by a church covenant he adapted to the Jamaican context. By 1814 his efforts had produced, either directly or indirectly, some 8,000 Baptists in Jamaica. At times he was harassed by the white colonists and by government authorities for “agitating the slaves” and was imprisoned, once for more than three years. While he never openly challenged the system of slavery, he prepared the way for those who did; he well deserves the title “Negro slavery’s prophet of deliverance.” Liele died in Jamaica. From this entry and reflection on Liele's life as a whole, I have a few thoughts:

While in Savannah, GA last week, my wife and I were privileged to take a tour of the First African Baptist Church in the United States. The one hour tour contained a stimulating lecture about this historic church (founded in 1773) and its place in America's religious and social history. A number of things stood out.

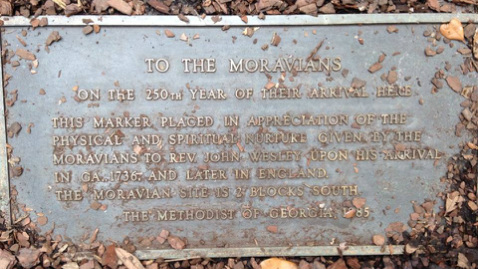

The founding pastor, George Liele, who also went on to be the first American Baptist missionary, was encouraged to study and also teach the Bible by his Christian owner Henry Sharp who was also a Baptist deacon. Sharp later freed Liele, which resulted in his missionary work in Jamaica. The structure was probably the first church building in America built by slaves for slaves. The present facility was also the first brick building in Savannah and bricks were hand carried up the steep incline from the Savannah River. As men made bricks at the river and other men did the masonry, it was probably women who transported these heavy loads. All of this labor took place at night after the slaves had already put in a full day's work. Church at First American Baptist was not only a spiritual event, but also a family reunion opportunity for African families that had been split up and sent to work for different owners. Many of the pastors in the church's history have also been leaders in society. For example, Rev. Emmanuel King Love, the church's sixth pastor believed in the value of education and was influential in the founding of Savannah State University, Morehouse College in Atlanta, and Paine College in Augusta. First African Baptist was also a starting point on the famous Underground Railroad--a route that led slaves out of the South toward freedom in Canada. According to the church's website: The ceiling of the church is in the design of a “Nine Patch Quilt” which represented that the church was a safe house for slaves. Nine Patch Quilts also served as a map and guide informing people where to go next or what to look out for during their travel. The holes in the floor are in the shape of an African prayer symbol known as a Congolese Cosmogram. In Africa, it also means “Flash of the Spirits” and represents birth, life, death, and rebirth. Beneath the lower auditorium floor is another finished subfloor which is known as the “Underground Railroad.” There is 4ft of height between both floors. The entrance to the Underground Railroad remains unknown. After leaving our tunnel, slaves would try to make their way as far north as possible. There are no records as to who went through the tunnel or how many. It is appropriate that this congregation used its facility to not only proclaim the gospel but to also fight against the social sin of slavery. It is great to see that First African Baptist continues today as an active church and we received a warm invitation to worship with this church community during our visit to Savannah. Below are some images from inside the church. While visiting Savannah, Georgia last week, I was encouraged to learn more about the church and mission history in this significant port city. Below are some brief reflections on the Moravians, John Wesley, and George Whitefield and their role in Savannah's spiritual history. According to the Visit Savannah home page: Savannah's recorded history begins in 1733. That's the year General James Oglethorpe and the 120 passengers of the good ship "Anne" landed on a bluff high along the Savannah River in February. Oglethorpe named the 13th and final American colony "Georgia" after England's King George II. Savannah became its first city. The plan was to offer a new start for England's working poor and to strengthen the colonies by increasing trade. The colony of Georgia was also chartered as a buffer zone for South Carolina, protecting it from the advance of the Spanish in Florida. Just a few years after its founding, missionaries and ministers began ministering in the city. In 1735, the Pietistic Moravians--arguably the first Protestants missions organization--arrived, lived communally, and ministered to the English as well as to native Americans. Though spending 10 years in the colony and enduring much hardship--including conflict with other Christians--perhaps their greatest legacy was their influence on another minister, John Wesley. Wesley, an ordained Anglican priest, came to serve as the minister at Christ Church in 1736-37. Though Wesley argues that he wasn't truly converted until after his return to England in 1738 (probably at a Moravian meeting), he nevertheless preached and gathered believers in his house for Bible study and prayer--a methodical (later "Methodist") approach to the Christian life. During the trans-Atlantic passage--either coming to or returning from Georgia--the ship carrying Wesley and where he served as chaplain was about tossed about in a great storm. Scared for his life, Wesley was impressed at the tranquility of the praying Moravians on board, who surely influenced him on his spiritual journey. From 1738-1741, Wesley's evangelist colleague and theological foe George Whitefield ministered in Georgia, preaching at Christ Church and also founding Bethesda Home for Boys--a school that instructed troubled boys from a biblical worldview but also taught them the practical trade of farming. Amazingly, the school continues today after two and a half centuries.

My article "Augustine on redemption in Genesis 1-3" was recently published by the South African theological journal Verbum et Ecclesia. Below is the abstract:

Many theologians, including those concerned with theology of mission, frame the drama of God’s story and mission (missio Dei) through the three major acts of creation, fall and redemption. Others add that the new creation ought to be regarded as a fourth act. Although this framework describes the entire biblical narrative, creation, fall and the hope of redemptionare, of course, quite present in the first three chapters of Genesis. In this article, I endeavored to engage with the commentaries of the African church father Augustine of Hippo (354–430 CE) to grasp his thoughts on redemption in Genesis 1–3. In his Genesis works, Augustine was primarily concerned with clarifying the doctrine of creation and, relatively speaking, had far less to say about redemption. That said, Augustine was, quite interested with Scripture’s story of redemption in his magnum opus De Civitate Dei [City of God]. Thus, in this article, I explored two major questions: first, why did Augustine pay so little attention to redemptionin Genesis 1–3? Second, how did he articulate and relate redemption in these chapters? It was shown that while his primary focus was to articulate creation, his thoughts on redemption were probably limited some because of the insufficiency of his Old Latin Bible translation and perhaps because of other distractions in ministry. Furthermore, it was argued that Augustine’s doctrine of redemption was a subset of his discussion on creation – specifically, that the second Adam (Christ) brought new life to God’s image bearers affected by the fall of the first Adam. My aim was to establish Augustine’s thoughts on redemption as a point of dialogue for theologians of mission endeavoring to clarify a theology of mission. As most mission theologians do not consult Augustine in their work and as most early Christian scholars do not read Augustine missionally, this study offered fresh insights for both groups of scholars. Read the complete article HERE. Over the past few weeks, I've enjoyed reading Stephen Hildebrand's new book Basil of Caesarea, which is a great introduction to he fourth century missionary-monk-bishop's life and theology. I've written a formal review that should be out in a journal in the fall.

Basil was a coenobitic monk. That is, he valued community as the means of growth in Christian discipleship and the monastic life. The community was also the foundation from which he ministered--particularly to the poor, hungry, sick, and stranger in the region of Caesarea in Asia Minor. Hospitality played a central role as visitors from Asia Minor, Armenia, Syria and beyond were regular guests at his table. While showing Christian hospitality, Basil also saw this as an opportunity to witness to non-believers by demonstrating self control at the table (Hildebrand, 132; also Basil, Longer Rules 20.2). For those who joined Basil's monastic community, gluttony was not an option. Hildebrand writes: "Anyone who would enter Basil's community, then, must be possessed of a certain measure of self-control. Taking sexual continence for granted, he spends most of his time in the Rules treating self-control in regard to food. His monastic legislation here, however, remains flexible, according to the varying needs of the various members. The young and the old, the sick and the well, those with strenuous occupations and those will light, have different dietary needs. All, however, have the benefit of hearing the Scriptures read at mealtime to forestall any undue attachment to food." (Hildebrand, 132; Basil, Shorter Rules, 180). Ever struggled with over eating? Ever thought of reading Scripture at mealtime? Would feasting on Scripture help to keep other appetites in check? |

Archives

November 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed