posts

|

This past weekend at the southeast regional Evangelical Missiological Society meeting at CIU, I had the privilege to present a paper on oral and visual strategies used by the Celtic monks to evangelize the Picts of modern Scotland from ca. 600-900. This was my abstract:

When remembering the history of Celtic monasticism and mission, many are quick to recognize the rich literary tradition that accompanied the movement. Indeed, such works as Patrick’s Confessions, Adomnan’s Life of Columba and The Holy Places as well as the development of a few remarkable Gospel books—the Book of Kells, the Book of Durrow, and the Lindisfarne Gospels—lend credence to this claim. That said, far less attention seems to be paid to the oral emphases of Celtic monastic missions and, in particular, the Iona community and their mission to Picts. In this paper, following a brief narrative of mission and background on the Pictish peoples, I will argue that Columba (521-597) and his monks, despite their significant abilities in reading and clear commitment to it as part of their spiritual growth, were quite deliberate in engaging the visual and oral context of their Pictish hosts. To support this claim, two texts in particular will be explored and evaluated for their oral qualities—St. Martin’s cross and the Book of Kells. As this was an argument based on visual images, attached HERE is my presentation with images of Iona and the texts used by the monks in mission. I had the chance to see Switchfoot live last night in Charlotte--the second time in the last month. While that might indict me as a groupie, I just saw it as taking advantage of two chances to hear some quality rock n roll from one of my favorite bands. Plus, I looked at the tour dates on the back of my new t-shirt and they're not going to be around here again any time soon.

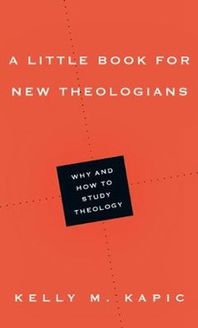

I was impressed at how different the show was, too from just four weeks ago. Some songs from the new Fading West album were worked into the live show and some older songs (Meant to Live, Hello Hurricane, Your Love is a Song) were interpreted in fresh, new ways. It's inspiring to see a band growing and continuing to create even when they're playing a similar play list night after night. My favorite song of the night was the last--World Where I Belong (have a listen above). As the last song on the Vice Verses album, it really completes an album that has a strong future hope emphasis. I love the mastery of these lyrics about the bodies we dwell in and and will give up when we die: But I'm not sentimental This skin and bones is a rental And no one makes it out alive The refrain, like a good Psalm, is filled with yearning and hope and resolution for how to live here and now: Until I die I'll sing these songs On the shores of Babylon Still looking for a home In a world where I belong As I sing along, I hear Augustine's admonitions from the City of God to persevere and be salt and light in the earthly city given our not yet fully realized citizenship in the heavenly city. We press on to grow in Christ and participate in God's mission because of this future hope. In reading Kapic's Little Book for New Theologians, he adds that we also worship and think about God (theologize) because of eternity: "The praise offered now comes from those laden with anxiety, while in heaven all are free from concern; here there is hope, in glory 'hope is realized'" (p. 33). Thanks Switchfoot for raising important questions in your music. This is a big little book--a must read for students beginning theological or seminary studies. In 10 chapters (easily read in one sitting each) and just over 100 pages, Kelly Kapic winsomely integrates the heart of theology with the how of it. This is timely because as often fragmented people, we fragment things like studying doctrine, worship, and sacrificial Christian service when they were never meant to be disintegrated. Built from his doctrine 101 course at Covenant College, the author wonderfully makes his case for a lived, worshipping theology by including the likes of Origen, Cyprian, Augustine, Gregory Nazianzen, Anselm, Luther, Calvin, Kierkegaard, Barth, Lewis in the conversation. After making the case for the why of theology in the first 4 chapters, Kapic takes the final 6 to discuss the characteristics of a theologian: one committed to faithful reason; prayer and study; humility and repentance; suffering, justice, and knowing God; tradition and community; and a love of Scripture. Given this overview, I'll comment on several things that I found especially helpful.

Theology is a pilgrimage. Christians focus on their "walk" as members of "the Way" (p. 32). As John Owen points outs, we like Moses want to see God but "we see only his back parts" (p. 35). That is, our theological understanding is limited at best. Kapic adds that "The praise offered now comes from those laden with anxiety, while in heaven all are free from concern; here there is hope, in glory 'hope is realized'" (p. 33). With this future hope in mind, we continue to worship God, ponder His ways, and grow and develop and occasionally change our minds during our theological journey. Faithful reason. Kapic helpfully writes, "In theology, reason rightly works in the service of faith; and because of this, faithful theology does not despise rational reflection" (p. 52). Following in the Augustinian tradition of faith seeking understanding, Kapic argues that faith should proceed reason; but yet the two work together toward a clear understanding of theology. Seeing doxology as the end of theology, he concludes chapter 5, "it becomes impossible to imagine theology that is not hungering and thirsting for communion with God" (p. 63). Prayer and study. Continuing Anselm's tradition of forging theological discourse in the form of a prayer, Kapic adds that "prayer makes faithful theology possible" (p. 67). He continues, "Here we speak not merely of times set apart when we fold hands and bow heads, but also a way of being" (pp. 66-67). That is, a theologian is always in the presence of God and in constant conversation with God even while also using the mind to articulate theology. Humility and Justice. In chapters 7 and 8, Kapic argues that the study of theology ought to produce humility in the theologian before God and others. If not, then there is a clear theological-spiritual problem. Related, true theology demands action--the practice of living out the Christian faith in the world and connecting with the "weak, hurting, and lonely" (p. 90). He concludes chapter 8 asserting we should allow "the call for sacrificial action to reshape our theology" (p. 92). Scripture. In the final chapter, Kapic concludes, "good, orthodox, and worship-inducing theology must be rooted in, sustained by and continually nourished through Scripture" (p. 107). The author appropriately concludes the book by offering a definition of theology: "an active response to the revelation of God in Jesus Christ, whereby the believer, in the power of the Holy Spirit, subordinate to the testimonies of the prophets and apostles as recorded in the Scriptures and in communion with the saints, wrestles with and rests in the mysteries of God, His work, and His world" (p. 121). So let us wrestle and rest as we do theology. While ministering in Bosnia in the Spring of 2011, I visited the Mehmed Paša Sokolović Bridge, the site where some 2500 Bosnian Muslims were massacred by the Serbian army and their bodies thrown in the the Drina River. While it was difficult to imagine such an atrocity happening in the mid-1990s, it was even more troubling to cross the bridge and find this monument dedicated to the bravery of the Serbians. As we gaze at the picture, we find a sword in one hand and a cross in the other--quite a statement of nationalism cloaked in Eastern Orthodox Christianity. As I looked at the monument, I could not help but think of the Emperor Constantine who also put cross-like symbols on the armor of his soldiers--a symbol of an ever growing Christendom (the marriage of church and state) in the Roman Empire that would fully flower by the end of the first millennium.

The question that I wrestled with in Rethinking Constantine was did the rise of Constantine signal the end of Christian mission as we understand it in the Scriptures? This is a complicated question with no simple answers as the abstract from that chapter shows: Christianity is a missionary faith. This is certainly evident from the “Great Commissional” type passages of Scripture, verses preached from and visibly posted in modern evangelical missions conferences, but even more so from the overall thrust of Scripture. That is, the mission of God (missio Dei) is the grand narrative of the Old and New Testaments and thus, in the opinion of some scholars, Scripture should be read with a hermeneutic of mission. Whether this approach to Scripture is fully accepted or not, mission remains in the DNA of the Christian faith and the Christian movement prior to the fourth century demonstrated this value. But did mission—proclaiming the death, burial, and resurrection of Christ and ministering to all nations in word and deed—cease with Constantine’s conversion and his giving Christianity a preferred status within the Roman Empire? Did Christendom, which expanded through political, military, and economic power replace Christian mission? In this chapter, I will argue that Christian mission did continue past Constantine, though the narrative certainly becomes more confusing following his rise to power. Beginning with a working definition of mission, I will discuss some representative elements of this diverse history showing examples of Christendom that appear to abandon mission altogether. However, this inquiry will largely reveal accounts of missionaries working within a state-church paradigm or at least approaching mission in full view of political authorities. In terms of scope and limitations, I will focus on missions within or from the Roman Empire from the fourth to eighth centuries. Finally, in my concluding section I will offer some points of reflection for modern Christians, particularly evangelicals, contemplating the history of missions. Learn more about the book HERE or HERE.  In chapter four of Rethinking Constantine, Jonathan Armstrong contributes an interesting chapter entitled: "Reevaluating Constantine’s Legacy in Trinitarian Orthodoxy: New Evidence from Eusebius of Caesarea’s Commentary on Isaiah." Challenging some modern depictions of Eusebius of Caesarea and, in turn Constantine, Armstrong summarizes his argument in the chapter by writing: Estimations of Constantine’s legacy in the theological definitions forged at the Council of Nicaea have differed markedly. On one hand, some historians view Constantine as a Machiavellian politician, orchestrating his every maneuver solely to achieve greater power for the imperial office. Other historians have portrayed Constantine as a man of genuine faith, legitimately invested in the theological issues debated at the council . . . Recent accounts aimed at a more popular-level audience generally fail even to give real consideration to the viewpoint that Constantine may have been motivated by theology in any of his political decisions. In this essay, I have attempted to demonstrate that the evidence from Eusebius of Caesarea’s Commentarius in Isaiam (Commentary on Isaiah) points toward the conclusion that Eusebius had fully accepted Nicene orthodoxy at the end of his life, and this in turn supports the conclusion that Eusebius’ depiction of the role that Constantine played in the council in Vita Constantini (Life of Constantine) was not dramatically rewritten to mask Eusebius’ own unorthodoxy. In removing reason to suspect Eusebius of compromised orthodoxy, this same evidence removes reason to suspect that Eusebius’ portrait of Constantine’s advancement of orthodoxy at the Council of Nicaea was fabricated for reasons of political expediency. Much of Armstrong's argument is founded on conclusions he developed after translating Eusebius' Commentary on Isaiah into English.  In chapter two of Rethinking Constantine, Brian Shelton examines the portrait of the Roman emperor from the perspective of the lesser known church father Lactantius (ca. 240-ca. 320). In his article entitled, "Lactantius as an Architect of a Constantinian and Christian 'Victory over the Empire,'" Shelton writes: The historic events leading to the accession of Constantine irrevocably rely on a crucial but obscure rhetorician who taught in Nicomedia. It was a contemporary voice from North Africa that entered this eastern city into the court and life of the emperor, a voice of erudition and of suffering. The writings of Lactantius offer both a philosophical and historical report on the pursuits of the Roman leader who came to champion Christianity in an empire that resisted the new religion. In particular, his writings shaped Constantine’s understanding of the faith and influenced the later religious policies that he would enact. Scholars have established Lactantius as a contributor to the genius of a new religious empire and an inescapable historical voice of that evolution, but they are only beginning to scrutinize his exact influence. This chapter seeks to identify and disaggregate the con- tribution of Lactantius in his fourth-century influence and in his twenty- first-century legacy. In particular, it depicts this influential turn-of-the-fourth-century philosopher using a paradigm of architectural narrative. This is the notion that a historian writes in a way with intentional design, employing a metanarrative that creates not the events but the blueprint of those events— the frame for understanding, the interpretation, the significance, the divine providence of the events, or, to use the language of historical interpretation of Earle Cairns, “history as the product of inquiry.” Yet, for Lactantius, this is not vaticinium ex eventu or a theological spin on events crafted by the victors, but he was himself the champion for a cause of religious freedom that he was able to affect and witness fulfilled in his lifetime. In this way, a historian like Lactantius can be seen as a “narrative architect.” He designed a modified empire based on religious idealism but also records the impulses of the era in a way that history will forever view the development of this new empire. This essay, with an architectural theme, will consider his role as designer, as builder, and as narrator. After dealing with his role in the paradigmatic imperial shift, it will summarize his place in the edifice that we call history. Read more HERE. In the opening chapter of Rethinking Constantine, Glen Thompson writes an article entitled "From Sinner to Sinner? Seeking a Consistent Constantine." Dealing with the oft debated question of the sincerity of the emperor's conversion and Christian faith, Thompson (p. 5) summarizes his aims:

Seventeen hundred years after gaining control of the western Roman world, Constantine remains one of only a handful of Roman emperors whose name is still widely recognizable. This is due primarily to the new relationship that he formed between himself, the Christian church, and the empire and its legal system. Yet even some of the most basic aspects of that relationship are still hotly debated by scholars. This chapter presents a brief overview of the past several decades of Constantinian scholarship and then addresses several areas where history and theology converge and where consensus is still lacking. In particular, an Augustinian approach is used to examine the motives for and timing of Constantine’s conversion and to evaluate his Christian “walk.” The final section examines how both Christians and pagans viewed the emperor in the years following his reign, and this serves as a further check on the earlier sections. To this, I add in the book's introduction: Though approaching the issue historically, Thompson interprets Constantine's story within the Lutheran framework of simul justus et peculator--that followers of Christ (even monarchs) are righteous sinners. Read more HERE. |

Archives

November 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed