posts

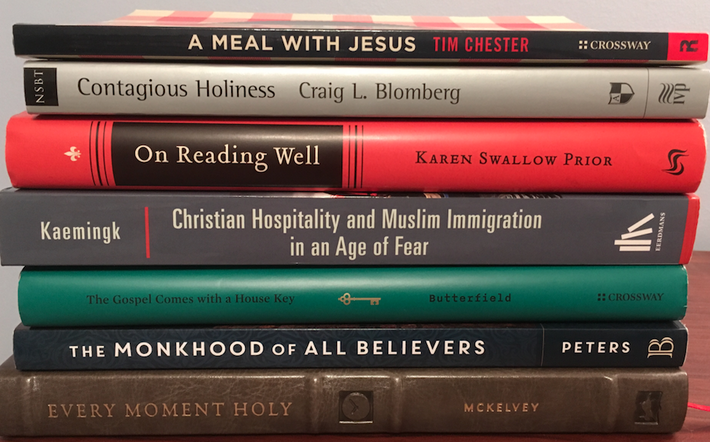

2018 was a great year for books. I’m grateful for new books (and others that were new to me). I tended to read in my field (history, mission, theology) but I branched out a little, too. In no particular order, these were my favorite reads this year. Brian Stanley, Christianity in the Twentieth Century. Stanley’s aim is to evaluate the “multiple and complex ways in which the Christian religion and its institutional embodiment in the Christian churches have interacted with the changing social, political, and cultural environment of the twentieth century” (2018: 3–4). To do this, he chooses fifteen themes that show how the church responded to the changing twentieth-century world, offering two case studies for each theme to make his point. He succeeds in providing the reader a rather comprehensive picture of twentieth-century global Christianity, including some places and people that may not get as much attention in other survey works (e.g., Polish Catholics, African Orthodox Christians, Australian Anglicans). My full review HERE. Greg Peters, The Monkhood of all Believers. Playing off some treasured Protestant language, Peters argues that though every Christian is not a monk in the institutional sense, monastic values are central to the Christian experience. Borrowing Martin Luther’s words, a Christian can be a monk but not a monk. I am a fan of Greg Peters’ scholarship and I learned much in this new work from his careful interaction with a breadth of sources—from early Christian monks, Russian Orthodox thinkers, Protestant Reformers, and Anglican sources. Peters successfully shows that the monastic impulse is present across Christian traditions. My brief review HERE. Ben Myers, The Apostles’ Creed. Breaking down each line of the creed, Myers’ engages Scripture and also leans on the thought of church fathers such as Ireneaus, Origen, Gregory of Nyssa, and Augustine. We grasp how the creed was articulated in the face of challenges from Gnosticism, Marcionism, Novatianism, and others. I think what I appreciated most was Myer’s ability to discuss the ancient creed with 21st century cultural concerns in mind: individualism, gender identity, and the material world. Myers’ presentation of the creed—and the gospel—was winsome, dogmatic, and relevant. My brief review HERE. Rosaria Butterfield, The Gospel Comes with a House Key. Butterfield explores “radically ordinary hospitality” which she defines as “using your Christian home in a daily way that seeks to make strangers neighbors, and neighbors family of God” (2018:31). With much biblical reflection, she offers a concrete model of hospitality offered on her street in Durham, North Carolina. Craig Blomberg, Contagious Holiness: Jesus’ Meals with Sinners. After surveying meals and hospitality practices in the Old Testament, Blomberg offers a thorough study of Jesus’ meetings at table with sinners and outcasts in the Gospels. Tim Chester, A Meal with Jesus. A practical work, Chester explores Jesus’ table ministry in Luke’s Gospel. Chester’s book reads like a short sermon series and a basis for his missional community church planting ministry. Karen Swallow Prior, On Reading Well. In this compelling work, Prior invites the reader to the joyous habit of reading. Urging “promiscuous reading,” Prior guides the reader through a survey of classical literature and a pursuit of virtue. The author integrates a love for God, Christian virtue, and literature. I was personally challenged to add more fiction (and imagination) to my reading diet. Douglas Kaine McKelvey, Every Moment Holy. My wife and I picked this up at an Andrew Peterson concert in the Spring. A supplement to our morning devotions, we have enjoyed this book of liturgy and prayers for many of life’s occasions. This tool reminds us that we live continuously in God’s presence thus making every moment an opportunity for holiness.  Brian Stanley. Christianity in the Twentieth Century: A World History. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2018. xxi + 477 pp. £27.00/$35.00. [review originally published in Themelios 43:3 (December 2018), 534-535]. Brian Stanley, respected historian of world Christianity and professor at the University of Edinburgh, invested six years producing his latest work, Christianity in the Twentieth Century. Stanley’s two previous works--The World Missionary Conference, Edinburgh 1910 (Grand Rapids, IL: Eerdmans, 2009) and The Global Diffusion of Evangelism (Downers Grove, IL: Intervarsity Press, 2013)—also explore issues of twentieth-century world Christian and mission history. Stanley’s aim is to evaluate the “multiple and complex ways in which the Christian religion and its institutional embodiment in the Christian churches have interacted with the changing social, political, and cultural environment of the twentieth century” (pp. 3–4). To do this, he chooses fifteen themes that show how the church responded to the changing twentieth-century world, offering two case studies for each theme to make his point. In the opening chapter, the author shows how British and American Christianity were affected by the First World War. Next, with a focus on Poland and Korea, he discusses the dynamics of Christianity and nationalism (ch. 2). The following three chapters consider prophetic and revival movements in Africa and the South Pacific (ch. 3), state-imposed secularization in France and the Soviet Union (chap. 4), and faith trends and church attendance in Scandinavia and the United States (ch. 5). He then explores church unity in India and China (ch. 6), racism in Nazi Germany, genocide in Rwanda (ch. 7), and the plight of Christian minorities in Egypt and Indonesia (ch. 8). Stanley continues his study by articulating twentieth-century mission theologies (ch. 9), exploring liberation theology in Latin America and Palestine (chap. 10), and discussing justice and the gospel issues in South Africa’s apartheid state and among Canada’s first nations population (ch. 11). He devotes one chapter to questions about the ordination of women in Australia and the gay rights in American churches (ch. 12). In the remaining chapters, he discusses global Pentecostalism (ch. 13), Eastern Orthodox Christianity (ch. 14), and the impact of global migration on the church (ch. 15). He concludes the book with a concise and summative chapter that brings the work together. Christianity in the Twentieth Century is a rich and thorough resource. Though Stanley limits himself to fifteen themes and two case studies per theme, he succeeds in providing the reader a rather comprehensive picture of twentieth-century global Christianity. This includes some places and people that may not get as much attention in other survey works (e.g., Polish Catholics, African Orthodox Christians, Australian Anglicans). Though Stanley adequately narrates the story of world Christianity in the last century, his many smaller nuggets of historical insights throughout the work are especially compelling. For example, he shows how WWI fractured the mission unity garnered from the 1910 Edinburgh World Missionary Conference and particularly alienated German missionaries from their European and North American counterparts (pp. 14–15). Also, he asserts that Egyptian Coptic Christians learned to be resilient as a religious minority by looking to their monastic past, to the desert fathers who remained firm in their faith amid periods of Roman persecution (p. 181). Stanley also questions the commonly held view that global Pentecostalism originated from the 1906 Asuza Street revival in Los Angeles. He points to other factors and spiritual movements that encouraged this expression of Christianity (pp. 291–92). Finally, Stanley shows how Eastern Orthodox practices, particularly the “Jesus Prayer,” spread to Europe during the middle of the century because of the large number of Russian Christians interned in German prison campus during WWI (p. 315). I have just two minor critiques. First, though Stanley gives space to both Latin American liberation theology movements and the holistic missiology of Latin American evangelicals (Padilla, Escobar, Costas) at Lausanne 1974 (pp. 210–13, 223–31), he makes no connection between the thought and practice of these two movements. This is especially surprising given his good argument for the Protestant influences on liberation theology within the Roman Catholic Church. Second, while the author does a good job of surveying twentieth-century global Christianity, his work still seems a bit overly focused on the church in America. The biggest twentieth-century Christian story was the church in Africa. This deserves more space. In sum, Stanley has produced an inviting, well-written, and excellent survey of twentieth-century global Christianity. Scholars, professors, and graduate students of Christian history will greatly benefit. Paired with primary source readings, this fifteen-chapter book would be a great anchoring text for a graduate or seminary level course on Christianity in the twentieth century. |

Archives

November 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed