posts

Eric O. Jacobsen. Three Pieces of Glass: Why We Feel Lonely in a World Mediated by Screens. Grand Rapids: Brazos, 2020. xv + 265pp. $19.99 [originally published in Evangelical Missions Quarterly, January 2021]. In this engaging new work, Eric Jacobsen, a presbyterian pastor in Tacoma, Washington, presents a vision for belonging and connecting in a relationally fragmented 21st century North American culture. In the closing pages of the work, he states the problem: “We live in a culture that is experiencing a profound crisis of belonging largely because we have insulated and isolated ourselves from people, place, and story by encasing ourselves behind three pieces of glass—windshields, TV screens, and smartphones” (251). Following an opening section in which he defines belonging in private and public contexts (part 1), he unpacks a vision of kingdom (part 2) and gospel (part 3) belonging with rich support from Scripture. From there, he discusses the crisis of belonging in the 21st century western world—the relational deficiencies that have developed because of technology (part 4). In the final sections, Jacobsen offers encouragement and constructive steps for achieving belonging (parts 5 and 6). He concludes: “We desperately need something or someone to break through these elements of our self-imposed exile and draw us in to the beckoning that we most desperately want . . . we can pray and work that we too would experience connection to people, place, and story right where we live” (251-52). Most readers would affirm Jacobsen’s claim that technology (smartphones, TVs, cars) have contributed to growing isolation, loneliness, diminished social skills, and even mental illness among 21st century North Americans. To support his thesis, the author makes a number of insightful points. First, he shows how post-World War II city and neighborhood planning has contributed to isolation. Cul-de-sacs within suburban neighborhoods have created unwelcome barriers toward outsiders. The construction of homes with attached garages have allowed suburban dwellers to come and go without any neighborly interactions. During half hour commutes to work, drivers often demonstrate unkindness and even road rage toward other commuters. Some of them display similar unkindness on their phones in social media interactions with people they do not know. Second, Jacobsen shows how relationships—even acquaintances or casual friendships—have suffered in the public or civic sphere. Because people are not commuting or shopping on foot, they no longer have relationships with grocery clerks, butchers, or neighbors along the way. Jacobsen’s book provides much food for thought for pastors, church planters, missionaries, and believers desiring to have a witness in their communities. As we long for our neighbors to believe the gospel and belong to the body of Christ, it is helpful to recognize the structural, technological, and cultural barriers that have emerged. Many, like Jacobsen and his family, are moving into cities with high walking scores. They are striving to belong in the public sphere by commuting on foot and engaging public spaces and institutions, and through their life and witness, they are seeking the “peace and prosperity” of their city (Jer 29:7). For Further Reading James K.A. Smith. You are What You Love: The Spiritual Power of Habit. Grand Rapids: Brazos, 2016. Andy Crouch. The Tech-Wise Family: Everyday Steps for Putting Technology in its Proper Place. Grand Rapids: Baker, 2017. Jay Pathak and Dave Runyon. The Art of Neighboring: Building Genuine Relationships Right Outside Your Door. Grand Rapids: Baker, 2012.  October 9-10, I am privileged to participate in the virtual annual meeting of the Evangelical Missiological Society on the theme, "The Past and Future of Evangelical Mission." I am presenting a forward looking paper entitled, "Mission at and from the Lord’s Table: A Eucharistic Foundation for Mission." From the introduction: “And now, Father, send us out to do the work you have given us to do, to love and serve you as faithful witnesses of Christ our Lord” (BCP 2019, 137). In these words, the post-communion prayer in the Anglican Eucharistic liturgy, believers receive and declare their call to mission. Having given thanks to the Father and feasted at the Lord’s Table, believers continue their worship through witness. Eastern Orthodox theologians call this the liturgy after the liturgy. While mission is an outcome of communion at the Lord’s Table, the mission of God (Father, Son, and Holy Spirit) also begins at the Table. With Christ as host, the Eucharist becomes a space where believers may be renewed in the gospel, tasting and seeing that the Lord is good (Ps 34:8). The Table may also be a welcoming space where non-believers not participating in the Eucharist may come and see the gospel. In this paper, following a brief discussion on the Passover, Last Supper, and Lord’s Supper in the Scriptures and early Christianity, I discuss mission at and from the Lord’s Table, which will invigorate mission practice. Read an entire draft of the paper HERE.  In this inviting new book, Andrew Wilson describes a vision for fusing two Christian traditions: “eucharistic . . . historically rooted, unashamedly sacramental, deliberately liturgical, and self-consciously catholic” with “charismatic . . . to expect spiritual experience, pursue and use the charismata [gifts of the Spirit], live and pray as if angels and demons are real and express worship to God with all . . . joy” (18). He begins (chap 2) by showing how our good Father gives us gifts (the gospel, the sacraments, spiritual gifts) for which we give thanks and become stewards. Wilson then unpacks a bit the fruit of the Spirit of joy (chap 3). Though Jesus was a man of sorrows, and in this world we will have trouble (pain, loneliness, grief), the Christian ought to expect joy in God’s presence. Here’s my favorite quote from the book: "Like wine, both the sacraments and the Spirit bring joy. Like wine, they lead the church into anticipation and thankfulness, celebration and song. Like wine, they witness to the new creation that is coming, offering us a glass from the early harvest while we wait for the full vintage to be bottled in summer. The early church, we could almost say, was oenologically Eucharismatic" (49). Next, Wilson makes a case for the importance of eucharistic worship (chap 4). Borrowing heavily from James K.A. Smith’s claims that we are liturgical animals shaped by our loves (75-80), Wilson asserts that liturgical worship practices best fit how God has wired us. He then discusses the relevance of charismatic worship (chap 5). With a faithful survey of the church fathers of the first five centuries who testified to tongues, miracles, and healing, Wilson presents a fine continuationist argument for the gifts of the Spirit (chap 6). He closes the book with a brief proposal for how eucharistic and charismatic worship can be fused (chap 7). Wilson puts forth a great vision for the compatibility of liturgical and charismatic worship. Indeed, in historic movements of renewal and revival, we do observe traditions crossing (i.e. Moravian Lutherans, Charismatic Catholics) and the whole church being strengthened by the best of each tradition. Why can’t liturgy (i.e. the prayers of the people) get a little rowdy in the joy of the Holy Spirit? Why can’t experiential charismatic worship be rooted in the ancient creeds and framed by collects? My only quibble with the book is that Wilson seems to run out of gas on p. 124 and admits difficulty pointing to working models of his vision. Interestingly in another new book, Ever Ancient Ever New, Winfield Bevins covers some similar themes (see 141-155) and points to liturgical churches that are also charismatic (Holy Trinity Brompton, UK; Catholic Charismatic Renewal, USA) and charismatic churches that have embraced liturgy (Trinity Anglican Mission, Atlanta; and New Life Downtown, Colorado Springs). All said this is a well-written, even funny, book that raises vital questions of church life and practice. Pastors, missionaries, and even professors (I did) will get a lot out of it. My reading for the past year tended to support research projects (on hospitality and mission, and suffering and martyrdom). I also enjoyed some rich devotional reading. While much of my reading came in the form of journal articles and book chapters, I also benefited from whole books. In no particular order, these were my favorite reads of 2019.

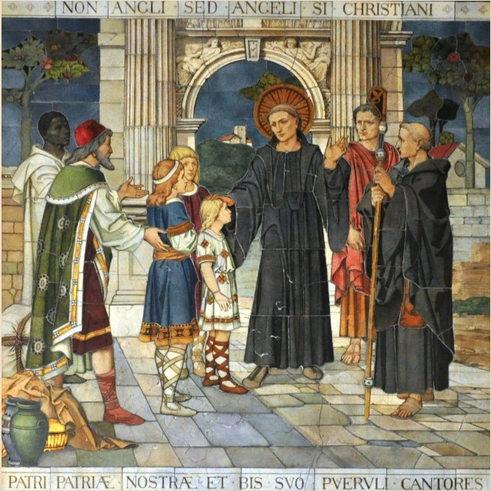

The Rule of Benedict: An Invitation to the Christian Life (George Holzherr, OSB). During the summer I attended a conference on monasticism and the church to explore how those who are not monks might emulate some monastic rhythms and values. So, for the summer, I read this translation of Benedict’s Rule that also included a very thorough commentary which situated Benedict’s monastic vision and practice within broader monasticism. The Lord’s Prayer: A Guide to Praying to Our Father (Wesley Hill). The second release in Lexham’s Christian Essentials Series, Wesley Hill takes the reader through a meditation on the Lord’s Prayer breaking down each line of it (the invocation, seven petitions, and closing doxology). After several years of using the Our Father as the framework for daily prayer in our home, I was anxious to dig into this. For me the most transformational chapter that has affected by prayer life was petition four, “Give us this day our Daily Bread.” Hill notes that more than a prayer for material provision, it is a reminder to feast on Christ the bread of life (Jn 6:48-51); to allow the Lord Jesus to satisfy our souls with His nourishing presence. This reality is powerfully symbolized when we take the bread during the Eucharist. Hill adds: “In the Eucharist, Jesus puts Himself in our hands so we know exactly where to find Him” (p. 55). On the Road with Saint Augustine: A Real-World Spirituality for Restless Hearts (James K.A. Smith). I’ve been a big fan of Jamie Smith since reading You are What your Love--a game changer in my spiritual life. In this new award-winning back, he does a faithful and concise job of making the pre-modern church father Augustine of Hippo a conversation partner for thinkers (especially existential philosophers), and all spiritual seekers. Augustine’s prodigal journey triggers our reflections on our own prodigality. Smith also rightfully urges a hermeneutic of migration. That is, we are wanderers in this world—existentially or literally—and we ought to read Scripture through these lenses. Though dense in content, the book was engaging, and it was over before I realized it. The 21: A Journey in the Land of the Coptic Martyrs (Martin Mosebach). While researching suffering in the modern global church, I read Mosebach’s careful account of the 21 martyrs (20 Egyptian Copts and one Ghanaian believer) who were executed by ISIS on the beach in Libya in 2015. My heart broke for how these impoverished men, working abroad in Libya to provide for their families back home in Egypt, were brutally murdered. I was inspired by their commitment to the Coptic liturgy, which they sang daily while working in Libya and during their period of captivity. In their suffering and martyrdom, they worshipped. I was also surprised that the Muslim government of Egypt paid to build a church in their honor in their hometown. Remembrance, Communion, and Hope: Rediscovering the Gospel at the Lord’s Table (J. Todd Billings). Billings wrote this to invite the church (particularly his Reformed tradition) to spiritual renewal by a deepened reflection on and practice at the Lord’s Table. He strongly draws upon Calvin’s teaching of the Lord’s real presence in the Supper. I love Billings’ admonition to actively participate in the Eucharist: “The Lord's Supper is more than a mental act of meaning making. It is an embodied practice in community, engaging all our senses in the context of worship” (p. 17). The Eucharist: Sacrament of the Kingdom (Alexander Schmemann). It seemed like every of author I read this year was quoting Schmemann so I decided to go to the source itself. In this classic work, first translated into English in 1987, Schmemann captures the Russian Orthodox theology of the Eucharist. His work is really a street level theology of the Eucharist since he constructed it from his own experience of Eucharistic worship. Schmemann frames the work around the sequential stages of the Liturgy. I especially appreciated the preaching of the gospel during the homily and in the Eucharist itself. Come, Let Us Each Together: Sacraments and Christian Unity (George Kalantzis and Marc Cortez, eds.). This work is the fruit of the 2017 Wheaton Theology Conference—a discussion of the sacraments and Lord’s Table from various church traditions (Protestant, Catholic, Orthodox, free church) and how the global church might arrive at unity around the Lord’s Table. I particularly enjoyed Cherith Fee Nordling’s chapter (pp. 78-93) on Jesus acting as host at the Lord’s Table. Jesus welcomes us at the Table not only as the crucified, buried, and risen Savior, but as the ascended Lord who sits at the right hand of the Father. I also appreciated Paul Gavrilyuk’s call for the Eucharist to unite believers: “As an eschatological sign, the Eucharist has the potential to relativize all forms of existing human alienation; it is a purification of the fallen forms of unity (tribal, national, racial, political) that go against the believers’ new life in Christ (Eph 2:13-14)” (pp. 176-177). An eighth-century biography of Bishop Gregory I of Rome (540-604) attests that one day, before he was bishop, Gregory saw boys “with fair complexions, handsome faces, and lovely hair” being sold in the slave market in Rome.[1]Inquiring about their identity, he was told that they were angli (Anglo or English).Responding with a play on words, he declared, “they have the face of angels [angeli] and such men should be fellow-heirs with the angels in heaven.”[2]Though scholars regard this story as a legend, around 596, several years after becoming bishop of Rome, Gregory sent Augustine of Canterbury (d. 604) and a group of about forty monks on a mission to evangelize the English—the first cross-cultural mission ever initiated by a Roman bishop.

In this paper, my aim is to first present Gregory the Great as a mission-minded bishop and sender of missionaries. Next, I will describe the mission to England—the hardships, outcomes, and approaches to mission. Finally, as we consider mission amid global crises in the 21st century, what do we learn from Gregory’s monastic theology of mission, his commitment to the mission, and his care for the missionaries? [1]This story is also recounted by Bede in Ecclesiastical History 2.1. [2]Bede in Ecclesiastical History 2.1; cf. Mayr-Harting, Coming of Christianity, 57-58.  2018 was a great year for books. I’m grateful for new books (and others that were new to me). I tended to read in my field (history, mission, theology) but I branched out a little, too. In no particular order, these were my favorite reads this year. Brian Stanley, Christianity in the Twentieth Century. Stanley’s aim is to evaluate the “multiple and complex ways in which the Christian religion and its institutional embodiment in the Christian churches have interacted with the changing social, political, and cultural environment of the twentieth century” (2018: 3–4). To do this, he chooses fifteen themes that show how the church responded to the changing twentieth-century world, offering two case studies for each theme to make his point. He succeeds in providing the reader a rather comprehensive picture of twentieth-century global Christianity, including some places and people that may not get as much attention in other survey works (e.g., Polish Catholics, African Orthodox Christians, Australian Anglicans). My full review HERE. Greg Peters, The Monkhood of all Believers. Playing off some treasured Protestant language, Peters argues that though every Christian is not a monk in the institutional sense, monastic values are central to the Christian experience. Borrowing Martin Luther’s words, a Christian can be a monk but not a monk. I am a fan of Greg Peters’ scholarship and I learned much in this new work from his careful interaction with a breadth of sources—from early Christian monks, Russian Orthodox thinkers, Protestant Reformers, and Anglican sources. Peters successfully shows that the monastic impulse is present across Christian traditions. My brief review HERE. Ben Myers, The Apostles’ Creed. Breaking down each line of the creed, Myers’ engages Scripture and also leans on the thought of church fathers such as Ireneaus, Origen, Gregory of Nyssa, and Augustine. We grasp how the creed was articulated in the face of challenges from Gnosticism, Marcionism, Novatianism, and others. I think what I appreciated most was Myer’s ability to discuss the ancient creed with 21st century cultural concerns in mind: individualism, gender identity, and the material world. Myers’ presentation of the creed—and the gospel—was winsome, dogmatic, and relevant. My brief review HERE. Rosaria Butterfield, The Gospel Comes with a House Key. Butterfield explores “radically ordinary hospitality” which she defines as “using your Christian home in a daily way that seeks to make strangers neighbors, and neighbors family of God” (2018:31). With much biblical reflection, she offers a concrete model of hospitality offered on her street in Durham, North Carolina. Craig Blomberg, Contagious Holiness: Jesus’ Meals with Sinners. After surveying meals and hospitality practices in the Old Testament, Blomberg offers a thorough study of Jesus’ meetings at table with sinners and outcasts in the Gospels. Tim Chester, A Meal with Jesus. A practical work, Chester explores Jesus’ table ministry in Luke’s Gospel. Chester’s book reads like a short sermon series and a basis for his missional community church planting ministry. Karen Swallow Prior, On Reading Well. In this compelling work, Prior invites the reader to the joyous habit of reading. Urging “promiscuous reading,” Prior guides the reader through a survey of classical literature and a pursuit of virtue. The author integrates a love for God, Christian virtue, and literature. I was personally challenged to add more fiction (and imagination) to my reading diet. Douglas Kaine McKelvey, Every Moment Holy. My wife and I picked this up at an Andrew Peterson concert in the Spring. A supplement to our morning devotions, we have enjoyed this book of liturgy and prayers for many of life’s occasions. This tool reminds us that we live continuously in God’s presence thus making every moment an opportunity for holiness.  Brian Stanley. Christianity in the Twentieth Century: A World History. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2018. xxi + 477 pp. £27.00/$35.00. [review originally published in Themelios 43:3 (December 2018), 534-535]. Brian Stanley, respected historian of world Christianity and professor at the University of Edinburgh, invested six years producing his latest work, Christianity in the Twentieth Century. Stanley’s two previous works--The World Missionary Conference, Edinburgh 1910 (Grand Rapids, IL: Eerdmans, 2009) and The Global Diffusion of Evangelism (Downers Grove, IL: Intervarsity Press, 2013)—also explore issues of twentieth-century world Christian and mission history. Stanley’s aim is to evaluate the “multiple and complex ways in which the Christian religion and its institutional embodiment in the Christian churches have interacted with the changing social, political, and cultural environment of the twentieth century” (pp. 3–4). To do this, he chooses fifteen themes that show how the church responded to the changing twentieth-century world, offering two case studies for each theme to make his point. In the opening chapter, the author shows how British and American Christianity were affected by the First World War. Next, with a focus on Poland and Korea, he discusses the dynamics of Christianity and nationalism (ch. 2). The following three chapters consider prophetic and revival movements in Africa and the South Pacific (ch. 3), state-imposed secularization in France and the Soviet Union (chap. 4), and faith trends and church attendance in Scandinavia and the United States (ch. 5). He then explores church unity in India and China (ch. 6), racism in Nazi Germany, genocide in Rwanda (ch. 7), and the plight of Christian minorities in Egypt and Indonesia (ch. 8). Stanley continues his study by articulating twentieth-century mission theologies (ch. 9), exploring liberation theology in Latin America and Palestine (chap. 10), and discussing justice and the gospel issues in South Africa’s apartheid state and among Canada’s first nations population (ch. 11). He devotes one chapter to questions about the ordination of women in Australia and the gay rights in American churches (ch. 12). In the remaining chapters, he discusses global Pentecostalism (ch. 13), Eastern Orthodox Christianity (ch. 14), and the impact of global migration on the church (ch. 15). He concludes the book with a concise and summative chapter that brings the work together. Christianity in the Twentieth Century is a rich and thorough resource. Though Stanley limits himself to fifteen themes and two case studies per theme, he succeeds in providing the reader a rather comprehensive picture of twentieth-century global Christianity. This includes some places and people that may not get as much attention in other survey works (e.g., Polish Catholics, African Orthodox Christians, Australian Anglicans). Though Stanley adequately narrates the story of world Christianity in the last century, his many smaller nuggets of historical insights throughout the work are especially compelling. For example, he shows how WWI fractured the mission unity garnered from the 1910 Edinburgh World Missionary Conference and particularly alienated German missionaries from their European and North American counterparts (pp. 14–15). Also, he asserts that Egyptian Coptic Christians learned to be resilient as a religious minority by looking to their monastic past, to the desert fathers who remained firm in their faith amid periods of Roman persecution (p. 181). Stanley also questions the commonly held view that global Pentecostalism originated from the 1906 Asuza Street revival in Los Angeles. He points to other factors and spiritual movements that encouraged this expression of Christianity (pp. 291–92). Finally, Stanley shows how Eastern Orthodox practices, particularly the “Jesus Prayer,” spread to Europe during the middle of the century because of the large number of Russian Christians interned in German prison campus during WWI (p. 315). I have just two minor critiques. First, though Stanley gives space to both Latin American liberation theology movements and the holistic missiology of Latin American evangelicals (Padilla, Escobar, Costas) at Lausanne 1974 (pp. 210–13, 223–31), he makes no connection between the thought and practice of these two movements. This is especially surprising given his good argument for the Protestant influences on liberation theology within the Roman Catholic Church. Second, while the author does a good job of surveying twentieth-century global Christianity, his work still seems a bit overly focused on the church in America. The biggest twentieth-century Christian story was the church in Africa. This deserves more space. In sum, Stanley has produced an inviting, well-written, and excellent survey of twentieth-century global Christianity. Scholars, professors, and graduate students of Christian history will greatly benefit. Paired with primary source readings, this fifteen-chapter book would be a great anchoring text for a graduate or seminary level course on Christianity in the twentieth century.  Playing off some treasured Protestant language, Greg Peters’ new book is entitled The Monkhood of All Believers. Continuing his monastic scholarship, which includes works such as The Story of Monasticism (2015) and Reforming the Monastery (2013), Peters argues that though every Christian is not a monk in the institutional sense, monastic values are central to the Christian experience. Borrowing Martin Luther’s words, a Christian can be a monk but not a monk. In the first part of his work, Peters thoroughly defines monasticism (chap. 1), narrates monastic history (chap. 2), and then discusses interiorized monasticism—the focus of every believer to have single-minded devotion to God (chap. 3). In part two, he spells out the meaning and practice of asceticism (chap. 4) and then shows that the notion of the priesthood of all believers is celebrated by Protestants and Catholics alike (chap. 5). In the final section, the author summarizes his case for monastic living for all Christians (chap. 6) and then discusses vocation in general and monastic vocation in particular (chap. 7). I am a fan of Greg Peters’ scholarship and I learned much in this new work from his careful interaction with a breadth of sources—from early Christian monks, Russian Orthodox thinkers, Protestant Reformers, and Anglican sources. Because of this engagement, Peters successfully shows that the monastic impulse is present across Christian traditions. My views on Christian monasticism’s fourth-century origins were challenged by Peters’ claims—via Augustine and Cassian—that monasticism can be traced to the habits of the earliest Christians in Acts 2 and 4. By arguing for first-century monastic Christianity, he does support his overall claim about the monastic-ascetic nature of Christianity—single-minded devotion to God. What’s a review without some critiques? First, though Peters’ research is thorough, his claims for the monkhood of all believers seem to rest on the thought of selected theologians (i.e. Paul Evdokimov and Raimon Panikkar in chap. 3) rather than the broader consensus of monastic history and thought. Second, the “I am a monk but not a monk” dichotomy began to unravel for me as I continued through the book. Indeed, monastic values and practices such as prayer, Scripture reading, and work ought to shape Christian spirituality for monks and non-monks alike. This is what Dennis Okholm was after in his work Monk Habits for Everyday Life (2007). While Peters aims to go farther than Okholm, calling for all Christians to be monks, in the end I didn’t see Peters’ work being terribly distinct from Okholm’s—everyday Christians can emulate monastic living to some degree. In short, while all Christians may follow the spiritual examples of monks and emulate some practices, I don’t think that makes all Christians monks. That said, as a non-monk who admires monastic spirituality and strives to apply some monk habits in my faith walk, I highly value this new book and Peters’ efforts to probe ancient and modern monastic thinking. I hope to see Greg Peters soon and talk about some of this more.  Andrew F. Walls. Crossing Cultural Frontiers: Studies in the History of World Christianity. Maryknoll: Orbis, 2017. xii + 284 pp. $32 [note: this was published in Themelios 43:1 (2018), 167-168]. Crossing Cultural Frontiers is the most recent work from Andrew Walls, an eminent scholar of history of Christian mission and world Christianity. Previously a missionary to Sierra Leone, Walls’ academic career has included professorships at the University of Edinburgh, Liverpool Hope University, and Afroki-Christaller Institute (Ghana). The present work is a “best of Walls” compilation comprising works published in other journals and books. In fact, it is the third such “best of” compendium. The previous two include The Missionary Movement in Christian History (1996) and The Cross-Cultural Process in Christian History (2002). The essays in the volume are grouped into three sections. In the first, “The Transmission of Christian Faith,” Walls argues for the multi-cultural and global nature of early Christianity (chap. 1), presents Origen as the father of mission studies (chap. 2), and discusses worldview, including how much of a believer’s culture and previous religion stay with them at Christian conversion (chap. 3). By juxtaposing Adamic (forced out) vs. Abrahamic (voluntary going) migration, Walls offers a theology of migration (chap. 4). Finally, he argues that studying Christian history is a cross-cultural exercise (chap. 5). In part two, “Africa in Christian Thought and History,” Walls explores world Christianity in the region of the world that he knows best. He explores a history of African discipleship through suffering (chap. 6), the eighteenth-century “Christian experiment” of the Sierra Leone colony (chap. 7), and nineteenth-century attempts to cultivate Christianity in the vernacular in West Africa (chap. 8). He completes the section by showing how African traditional religions began to be studied (chap. 9), and how the Ghanian scholar Kwame Bediako exemplified African Christian scholarship (chap. 10). In the final part, Walls focuses on “The Missionary Movement and the West.” In this he dedicates chapters to how western missions and missionaries are portrayed in English literature (chap. 11), John and Charles Wesley’s theology and practice of mission (chap. 12), and the legacy of mission literature—particularly Jonathan Edwards’ Life of Brainerd (chap. 13). In the remaining chapters, Walls discusses an African (Tiyo Sago) and Indian (Behari Lal Singh) scholar living in Britain and being exemplars of world Christianity (chap. 14), western missionaries in China committed to vernacular and indigenous Christianity (chap. 15), and the work of Harold Turner who sought to grasp indigenous Christianity with an eye toward traditional religions (chap. 16). In a brief concluding chapter, Walls reflects on the vocation of missiology. As only Walls can put it, he writes, “Missiologists are the magpies of the academic world; they invade the scholarly territory of their neighbors and steal their topics . . . the biblical field, the theological field, the historical field, and the practical field in the name of the study of mission . . . This also makes them academic subversives, upsetting harmony by raising new issues; introducing new perspectives and new data; identifying new questions and problems within established fields” (p. 259). There is much to appreciate in this collection of Walls’ essays and I will highlight two areas. First, Walls’ lifelong exploration of indigenous Christianity—the gospel at home in every culture—is well teased out in this volume. Beginning with the question, what does it mean to be a Greek (or African or other) Christian?, he illustrates this reality through a survey of the early church in general, and individuals such as Antony, Origen, Kwame Bediako, Tiyo Sago, and Behari Lal Singh (chaps. 1-2, 10, 14). He explores the eighteenth and nineteenth-century vernacular translation work of missionaries in West Africa and also China, including the struggles and failures to achieve local Christianity (chaps. 8, 15). In his study of conversion (chap. 3) and Harold Turner’s study of pre-Christian religions (chap. 16), he wrestles with the authentic cultural and religious identity of local Christians. In short, this volume offers a rich collection of case studies for indigenous and world Christianity. Second, Walls’ discussion on theology of migration (chap. 4) contained fresh insights. His paradigm of forced (Adamic) vs. voluntary (Abrahamic) migration sets a framework for peoples on the move in Scripture and throughout history. Further, his emphasis on Greater European Migration from the fifteenth to twentieth centuries is important because it offers a context for understanding colonialism and the founding of new nations, while also offering context for the reverse migration to Europe and the West which has taken place in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. These historical and theological reflections are needed by the church in the West today. To these points of appreciation, I raise two questions for critique. First, I applaud Walls for highlighting Origen as the father of mission studies (chap. 2). Origen showed how one could be thoroughly Christian and thoroughly Greek and thoroughly Egyptian and he praised the work of itinerant evangelists. However, can we call someone the father of mission studies who lacked personal and practical experience in cross-cultural mission engagement? Second, Walls has helped the reader understand the identity of a Christian believer situated in a local culture with a pre-Christian past (chap. 3). Conversion is a messy process as the gospel makes its home in a given culture. However, I think Walls could have given more space to discussing how and when local Christianity turns into idolatry or syncretism. To borrow from Walls, what does it look like for the gospel to be a pilgrim message (exhorting, critiquing, being prophetic) within a given context? All said, it was a pleasure to sit with Professor Walls on this journey. His call to do church history as a global, cross-cultural exercise (chap. 5) has certainly shaped this reader’s academic and professional path.  I'm honored that my article on Francis of Assisi, Christology, and mission was published in the July 2018 edition of Missiology: An International Review. The abstract reads as follows: In recent years, global theologians of mission have emphasized a posture of mission from below—missional engagement from a place of weakness and vulnerability. In part a reaction to the mistakes of Christendom and Christian mission’s alliance with political and economic power, mission from below aims to recover first-century mission that emulates the way of Christ and the apostles. This approach to mission is also relevant in contexts today where Christian freedom (for worship and witness) is limited by tyrannical or resistant governments. As we strive to be as wise as serpents and gentle as doves in contemporary mission, it seems fruitful to explore the theology of mission of a medieval Italian mendicant monk who ministered to Muslims during the Crusades. In this article, following a brief narrative of Francis of Assisi’s (1181–1226) life and journey in mission, I will focus on Francis’s Christology and how that shaped his approach to mission among Muslims and others. Finally, I will conclude with some reflections for what the church on mission today might gain from Francis. Read more HERE. |

Archives

November 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed