posts

|

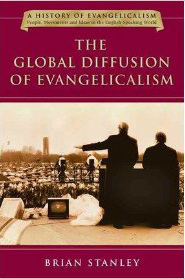

In this fifth book in the History of Evangelicalism series from Intervarsity Press, Brian Stanley aims to narrate the global expansion of evangelicalism within the English-speaking world since 1945. Stanley, who directs the Centre for the Study of World Christianity at the University of Edinburgh, is already known for his works The World Missionary Conference: Edinburgh 1910 and volume 8 of the Cambridge History of Christianity, World Christianities, c. 1815-1914.

This is an excellent, well-researched, highly readable volume from a global expert in the field and I appreciated having a number of gaps filled in in my understanding of twentieth-century global Christianity. While the reader can peruse the nine chapters which frame the book, I particularly appreciated: · Chapter 2 where the historic milestones between fundamentalism and evangelicalism are clarified. · Chapter 4 where the contribution of evangelical scholars—particularly those who teach in British universities—are noted. · Chapter 5 in which key defenders of evangelical theology, including Carl F.H. Henry and Francis Schaeffer, are discussed. Stanley ends the chapter by discussing the influence of C.S. Lewis, who greatly shaped twentieth-century evangelical imagination though Lewis himself would not have self-identified as an evangelical and certainly did not hold to the infallibility of Scripture. · Chapter 6 where the watershed Lausanne Congress on World Evangelization (1974) is carefully narrated. The reader will appreciate the initiative of Billy Graham, the majority world theological voices of Samuel Escobar, Renee Padilla and others, and the diplomacy and humility of John Stott who facilitated partnership between non-western and western church leaders. · Chapter 7 in which global charismatic and Pentecostal Christianity are described. Stanley remarks that the vitality of this movement has probably come as much through its renewed worship life and practices than through tongues, healing, and miracles. In addition to these broad themes, my favorite parts of the book include: · The testimony of Martin Lloyd-Jones (pp. 49-52), the Welsh physician turned pastor who was a Reformed Methodist committed to biblical exposition and who helped to nurture London Bible College. It seems that he could be all of these things because of having been touched by the Welsh revivals of 1904-1905. This characteristic of twentieth century evangelicalism—revivals and subsequent evangelism—seemed to unite many diverse evangelicals. · The story of the famous hymn, “How Great Thou Art,” which was heard by J. Edwin Orr at a conference in India in 1954 when sung by the Naga Baptist choir. Stanley writes (p. 81) that the song was “originally a Swedish hymn that had been translated, first into Russian, and from that into English by Stuart Hine in 1927. The hymn, introduced to India in about 1952, so impressed J. Edward Orr that he popularized it among the Christian public on his return to the United States . . . With the aid of George Beverly Shea’s solos, it soon became a favorite at the Billy Graham crusades and one of the most widely sung hymns in evangelical churches on both sides of the Atlantic.” It is not surprising that this song, which characterized twentieth-century evangelicalism, migrated from Sweden to India, via Russia, to the United States to be sung in evangelistic crusades around the world. My only critique of this work—rather related to the last point about “How Great Thou Art”—has to do with the scope of the work. I found it somewhat frustrating just to think about global English-speaking evangelicalism. As I read through the book, I thought that many of the points could have been even more deeply illustrated if Chinese-, Portuguese-, and Spanish-speaking Christians could have been represented. While I know an author and series editor must make some difficult choices about the scope of a work, I still must register this one complaint. That said, Stanley’s latest work is one of the best things I’ve read in 2013. Last week, a number of Saudi women formally protested the Kingdom's ban against women driving by getting behind the wheel, driving, and filming the whole thing. While the women were serious and articulate about their position, one Saudi comedian, Hisham Fageeh, satirized the events through his video "No woman, no drive," a parody of the famous Bob Marley song. With close to 9 million hits on YouTube in the last week, many around the globe also found his performance entertaining.

As I have reflected on this turn of events, I've had a number of thoughts. First, Fageeh shows us a side of the Muslim world that we don't always get in the West--a humorous side. Having lived among Arabs and Muslims for many years, I know that Arabs have a great sense of humor and tell some great jokes. Like Fageeh, who is clearly mocking his own society, many Arabs use humor to poke fun at and in a way cope with the frustrations and injustices in their societies. Historically though, they have not had a platform to broadcast their humor. So both the protesting women and Fageeh are using the same vehicle--social media and specifically YouTube--to tell the world about their worlds. Social media has given them an audience, a sense of empowerment, and an opportunity for free speech. While many women may not appreciate Fageeh's humor (because this is a serious issue for them), his 9 million hits on YouTube have only raised their issue even more. Hopefully, Westerners will get the irony and humor and realize that there is much diversity (that includes humor) in the Muslim world. |

Archives

November 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed