posts

David W. Shenk. Christian, Muslim, Friend: Twelve Paths to Real Relationship. Harrisonburg, VA: Herald Press, 2014. pp. 187, paperback, $14.99 Christian, Muslim, Friend is a recent work from David Shenk, a Mennonite missionary who has served in Somalia, Kenya, the USA, and who continually engages in peaceful dialogue with Muslim leaders around the world. Shenk has authored fifteen books and this new book is the fourth in his “Christians Meeting Muslims” series, which includes A Muslim and a Christian in Dialogue, Journeys of the Muslim Nation and the Christian Church, and Teatime in Mogadishu. In 2016, Christianity Today recognized Muslim, Christian, Friend as its book of the year for missions. In the book, Shenk lays out twelve paths or principles, each presented in a chapter, for engaging Muslims. Reflecting much on his five-decade journey of loving and commending Christ to Muslims, Shenk’s book offers much wisdom to Christ followers desiring to engage Muslims in the 21st century. In this brief review, I would like to highlight four themes that particularly struck me and seem instructive for the church today. Though chapter 6 focused on the place of hospitality in ministry to Muslims, hospitality was a pervasive theme throughout the book. Hardly a page goes by when Shenk is not relating accounts of having tea or meals with Muslim friends. Through showing and receiving hospitality—a strong cultural value in contexts where Shenk served but a central biblical value as well—many barriers to cultural and religious understanding were overcome which allowed for winsome gospel sharing. While chapters 10 and 11 emphasized the ministry of peacemaking, Shenk demonstrated throughout the book that peace was a foundational principle in his approach to Muslims. Evident in his tone toward initially hostile imams or even in the manner that he surrendered Mennonite Mission property to the government in Somalia during a revolution, Shenk’s posture of peace resulted in many open doors to share the person of Jesus the Messiah. Shenk’s emphasis on peace was coupled with a boldness for communicating the essentials of the gospel—particularly the person of Christ and his death, burial, and resurrection. In his ministry, Shenk did not hedge for a moment on the centrality of the cross—often a difficult issue for Muslims (see chaps. 7-9, 12). Remaining gospel-centered, Shenk consistently identified himself as a messenger for Jesus the Messiah, challenging his readers to pursue integrity in how they present themselves to Muslims (see chaps. 1-2). In short, for Shenk, a peaceful posture and a bold witness for Christ are quite compatible. Finally, throughout the book, Shenk demonstrates a good knowledge of Islam, the Qur’an, Hadith, Islamic theology, and Muslim traditions. However, he uses this knowledge to build bridges of understanding with Muslims while avoiding polemics. Though winsome to defend central gospel truths, Shenk refuses to attack Islam or Muslims in any way, laying the groundwork for respectful witness. In summary, Shenk’s book is quite accessible and ought to serve as basic reading for all followers of Christ desiring to understanding and minister to Muslims. It would also serve as an excellent text for a course on approaches to Muslim evangelism. Books often contain great arguments and claims that shape us. I'm particularly grateful for some new books that appeared this year that I was able to digest. Most of my reading is in the areas of global Christian history, theology, culture, and mission and the following were among my favorites in no particular order.

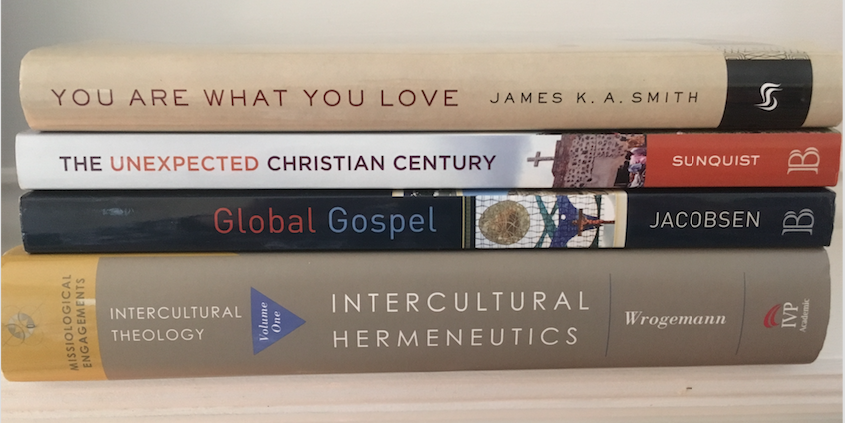

1. In Our Global Families, Todd Johnson and Cindy Wu offer Christ-followers the tools to understand and engage two families—the Global Body of Christ and the non-Christian, human family, while proposing a humble “faithful presence” approach to being on mission in a globalized world. See my brief review. 2. Douglas Jacobsen's Global Gospel presents a concise history and current status of the global church. He discusses the four main traditions within the global church (Roman Catholicism, Eastern Orthodoxy, Protestantism, and Pentecostalism) and then explores global Christianity geographically looking at Africa, Latin America, Europe, Asia, and then North America. I've a written review that is forthcoming in Evangelical Missions Quarterly. 3. I spent a good part of the year completing my own book, Missionary Monks, so I read a great bit on the history of monasticism, including Greg Peter's Story of Monasticism. Peters' stated aim is to craft a work “on the history of Christian monasticism geared toward a ressourcement of the tradition for the twenty-first century." I wrote a brief review here. 4. My monastic studies also benefited from George Demacopoulos', Gregory the Great: Ascetic, Pastor, and First Man of Rome. The author argues well that “Gregory’s ascetic and pastoral theology both informed and structured his administration of the Roman Church” and that Gregory synthesized well the contemplative life of a monk with the active life of a pastor. I have a forthcoming in Fides et Humilitas. 5. In Scott Sunquists's The Unexpected Christian Century, he attempts to sketch out the history of global Christianity in the twentieth century. This is a tall order indeed and I appreciate his approach to the “global century” that began with some 80% of the world’s Christians living in North America or Europe and ended with about 60% living in the Global South (Africa, Asia, and Latin America). I've written a short review here. 6. David Shenk's Christian.Muslim.Friend: Twelve Paths to Real Relationship ought to be read by every Christian who has ever watched a story on the news about Muslims. In the book Shenk shares insights from over five decades of engaging Muslims, demonstrating an effective combination of peacemaking, friendship, and bold Christian witness. See my review here. 7. Michael Bird's What Christians Ought to Believe: An Introduction to Christian Doctrine through the Apostle's Creed was enriching on a historical, theological, and devotional level. I found the book so accessible that our home fellowship adopted it to study this semester in our gatherings. I wrote some initial thoughts here. 8. Finally, the book that most impacted me spiritually this year was James K.A. Smith's You are what You Love: The Spiritual Power of Habit. As the title attests, Smith effectively shows that “Jesus’ command to follow him is a command to align our loves and longings with his." I've scribbled out some reflections here. Thanks to all of these authors for investing in my growth this year.  My CIU colleague Daniel Janosik has just published an important new work in the early history of Christian-Muslims relations in this survey of John of Damascus. Recently, Daniel and I participated together in a session on the doctrine of the Trinity in the history of Christian mission at the Evangelical Theological Society. In this post, he has responded to a few of my questions about John of Damascus: First Apologist to the Muslims. What led you to write this book? The book is a re-write from my Ph.D. dissertation. In my research I wanted to study the development of the Trinity in the Patristic age, especially as it relates to Apologetics, and I wanted to focus on how the Trinity was understood in the developmental phases of Islam. All of these factors came together nicely under John of Damascus, who was the chief theologian of the time and had written two treatises in regard to Islam and its opposition to Christianity. As the first Apologist to the Muslims, John’s views influenced generations of Christians after him, and he provided me with the eyewitness I needed in order to explore the early developments of the movement that became Islam. Who should read this? This is a scholarly treatment of John of Damascus, his writings on Islam (which I translated from the Greek), the development of Islam, and role of Apologetics in the development of doctrine. However, it is written in a way that is very accessible to the average lay person in the church. It is especially helpful for anyone who wants to understand how Islam was perceived at that time by the Christians and how history tells us a very different story from the traditional views of Islam that pervade so many books today. John was an eyewitness to these events, and as the chief financial officer of the Umayyad Empire under the caliph Abd al-Malik, he was able to reveal an insider’s understanding of what he called the “heresy of the Ishmaelites.” This is a book for anyone who wants to dig deep into the sands of history in order to clear away the layers that prevent us from understanding what really happened. What are your favorite parts of the book? One of my favorite parts of the book is going through the two treatises that John wrote on Islam, the Heresy of the Ishmaelites and the Disputation between a Christian and a Saracen. As an Apologist, I really enjoyed analyzing his arguments against Islam and gaining his perspective of the religion itself. It is so important for us today to learn from someone who was an eyewitness to the early events and one who may have influenced some of the first theological debates in Islam. I also enjoyed being able to explore the testimonies of other non-Muslims who lived at that time and wrote about their experiences with the monotheistic religion that became Islam. Looking through their eyes we can gain a perspective from the past that will help us reach out to Muslims today. What other writing projects are your working on at the moment? I am finishing up a book called A Christian’s Guide to Islam, which is geared for the general Christian in the church who wants to know everything necessary about Islam and Muslims in order to reach out to their Muslim friends with truth and love rather than fear. It is scheduled to be out in July 2017. I will also be working on a book that will provide a critical analysis and commentary on the text of John’s works on Islam.  It was one of the first papers I ever gave in an academic setting--a look at Possidius' Vita Augustini (LIfe of Augustine) as a fifth-century discipleship tool. There were only about 7 people in the room, which is not unusual for a patristics paper at an academic conference. But one of those 7 was Thomas Oden, editor of the Ancient Christian Commentary on Scripture (among many other works) and a scholar of early African Christianity. As I wrapped up my paper and opened it up for questions, to my horror Tom Oden had questions! Though I really wanted to find the nearest exit and get out of there, his question (something about the Pachomian influence on Augustine's monasticism) was straightforward and demonstrated his own curiosity and passion for growth as a scholar. Afterward, we chatted some more about African monasticism and he gave me his email address to stay in touch. More than anything, Tom Oden modeled for me humility, graciousness, and even a pastoral posture in scholarship. Later, I learned more of Oden's journey--from the anti-war movement in his college days, to being a theological liberal, to eventually embracing evangelical convictions. He arrived at what he called "paleo-orthodoxy" by reading the church fathers. Through editing the ACCS on Intervarsity Press, he helped a new generation of Christians to access the church fathers' writings, particularly how they thought about Scripture. Personally, I most profited from Oden's series on the early African church --How Africa Shaped the Christian Mind, Early Libyan Christianity, and The African Memory of Mark--and was honored to write reviews for each. Reflecting his passion for the faith and theology of the early church, Oden once stated that he wanted his tombstone to read: "He made no new contribution to theology." Professor Oden's contribution to theological and historical studies was, of course, significant and will continue to shape a new generation of students of the early church.  A few years ago, I had the privilege to travel to Iona, a tiny island located in the Inner Hebrides of western Scotland. For Christian history, it is important for being the place where sixth-century Celtic monks led by the Irish abbot Columba (521-597) established a monastery and also missionary base for evangelizing the Pictish people of the Scottish highlands. While preparing to go and study the mission history of the region, I asked my former doctoral supervisor about the best study resources on the island—things like libraries, study centers, and museums. Informing me that nothing quite that formal existed at Iona, he suggested that the most valuable study experience was to visit the island in December or January, stand outside and feel the cold North Atlantic air and wind, and imagine the sacrifice and service of the monks who went about their ministry in this environment. In many ways, that is what this book is about. We too want to stand in that cold place and walk in the shoes of Celtic and other missionary monks who sacrificed greatly to make the gospel known to the ends of the earth in their day. We want to grasp what it meant to pursue both a monastic and a missionary calling. Why is a book on missionary monks relevant for Christians today, especially for students of mission history and mission practitioners? As we journey through the pages of mission history—especially from about AD 500 to 1500—it’s impossible to do so without stumbling over quite a few missionary monks. In fact, I would argue that if we don’t have monks in this period, then we really have little to talk about in the way of Christian mission. So grasping the story of mission requires getting to know missionary monks. My intent in this work is to guide the reader through an introduction to the history of missionary monks and movements beginning in the fourth century and spanning to the middle of the seventeenth century. I want to tell the story of missionary monks—to meet them, learn about their contexts of service, consider their approaches to mission, discuss their challenges and victories, and grasp how they thought and theologized about mission. After narrating their stories, I will invite the reader to reflect on what can be learned from their experiences, including which of their strategies might be appropriated today in mission . . . In short, we will stand on the cold shores of Iona (and other places), consider what mission meant to them, and reflect on what their legacy means for us. Learn more about Missionary Monks here.  In chapter 9 of Controversies in Mission, veteran missiologist and anthropologist Miriam Adeney offers a moving reflection on Christian mission in the age of global migration--particularly illegal immigration. She writes: Today, eleven million people live in this land illegally. According to the law, they have no right to be here because they lack residency documents. Nevertheless, more continue to slip across our borders, including tens of thousands of children, who pushed up from Central America in 2014. This mobile population represents one of the great issues of our time. What is justice in relation to these people? What is mercy? How do we balance safeguarding our communities, upholding the law, and loving our neighbors? Furthermore, when we encounter migrants who are believers, how do we partner together in the new arenas of cross-cultural mission and ministry that are opening? These questions echo not only in America but worldwide as diasporas ebb and flow across many nations. This paper focuses on the federal Northwest Detention Center, a 1500-bed facility south of Seattle housing people scheduled for deportation. The detainees range from hardened criminals to those who have overstayed their student or work visas to others who lack complete papers simply because of irregularities in their journeys. For example, they may have no birth certificate because they were born in the middle of a war, and their non-English-speaking parents did not explain this. Whatever the reason, when the gates clang shut, the words over the entry to Dante’s inferno reverberate: “Abandon hope, all you who enter here.” Suddenly a man loses his income, his long term goals, and maybe even his spouse and children. Most detainees do not have attorneys. If they do not speak English, they may not understand what is happening. Most likely they will be dumped back in the land of their ancestors with or without money, or language, or family or friends. If that country has political or religious prejudices, they may undergo torture. Dante’s warnings ring loud. Yet a surprising and fruitful ministry with international reverberations has developed in the detention center. This paper briefly narrates that story. Several missiological themes appear:

Each of these themes deserves to be studied at much more length. Hopefully future research will continue this. Visit HERE to learn more about Controversies in Mission. |

Archives

November 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed