posts

In a significant 2006 article, missionary anthropologist Paul Hiebert (1932-2007) argued that a significant aspect of global mission should be mediating the work of global theology. He wrote: “missionaries are bridge persons, culture mediators, who stand between different human worlds . . . global discussions on contextualization need missionaries and global leaders who understand both the gospel and human cultures well and can bridge between them.” Since Hiebert’s article was written, a significant output of literature has come from evangelicals—both western and majority world scholars—on global theology. In this paper, I will show that John Stott (1921-2011), rector of All Souls, Langham Place, and global ambassador for mission in the Lausanne Movement, anticipated Hiebert’s admonition and, since the 1960s, acted as an early innovator in global theologizing. I will support this claim by focusing on Stott’s work within the Lausanne Movement and from that argue for Stott’s principles for facilitating global theology. Read the entire paper here: smither_stott_ets_2023.pdf Note: image from JohnStott.org. Jolene Erlacher and Katy White. Mobilizing GenZ: Challenges and Opportunities for the Global Age of Missions. Pasadena: William Carey Publishing, 2022. x + 182pp. Paperback. $14.99 (originally published in the July-September, 2023 edition of EMQ).

In Mobilizing GenZ, Erlacher and White aim to shed light on the identity of GenZ (those born between 1996 and 2010), to understand their virtues and struggles, and to offer insights on mobilizing them for the ongoing work of global mission. The book is divided into four main sections. In part 1, the authors offer context on the present state of missions, including the cultures of western sending countries and the current status of global Christianity. In part 2, they survey the identity, motivations, and faith of GenZ. Given this background, in part 3, they suggest relevant approaches toward mobilizing GenZ for mission. In the final part, they anticipate the future of mission and offer further insights for mobilization and sending. Mobilizing GenZ has some noteworthy strengths. First, the authors do a good job of describing GenZ and particularly showing how they are distinct from millennials. For example, while younger millennials are digital natives, this description is true of all of GenZ. They have never not been online. This has, of course, created problems such as a lack of social and communication skills, higher levels of anxiety, and greater exposure to pornography. Because of access to information, including online education, GenZ has the potential to be the most educated generation to date. While millennials are more concerned about addressing problems in the world, GenZ tends to be more individualistic and focused on happiness and stability. Though GenZ has had less real-world work experience than previous generations, they do tend to be more pragmatic and concerned about financial stability. Second, Erlacher and White build on this description of GenZ and provide some good insights into mobilizing the present generation for mission. Drawing from their professional strengths, they emphasize building long-term relationships with GenZ and coaching them toward connecting with their calling. Part of this coaching involves asking good open-ended questions. In Appendix D, they provide a list of good questions to ask. They also emphasize the need to connect with them through relevant media, including texting and social media. That said, the authors emphasize challenging GenZ to overcome biblical illiteracy and to become biblically rooted disciples. In addition to these affirmations, I have two critiques. First, in part 1, the authors rely on some rather dated material to sketch out the picture of the present context of global mission. They were particularly reliant on the 2009 edition of Perspectives on the World Christian Mission. Second, while the composite profile of Gen Z in part 2 of the work was helpful, it really did not go beyond what other authors such as Tim Elmore and Jean Twenge have already done. Who will benefit from reading this book? I recommend it to mission organization mobilizers, church mission committees or advocacy teams, church and parachurch leaders working among GenZ, as well as Christian university professors training students for global mission. Further Reading Barna Group. The Future of Missions: 10 Questions About Global Ministry that the Church Must Answer with the Next Generation. Ventura: Barna Group, 2020. Elmore, Tim and McPeak, Andrew. Generation Z Unfiltered: Facing Nine Hidden Challenges of the Most Anxious Population. Atlanta: Growing Leaders, 2019. Augustine’s Preached Theology: Living as the Body of Christ. By J. Patout Burns, Jr. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2022. xviii + 374 pp. $45.00. Hardcover (originally published in the Spring 2023 edition of the Criswell Theological Review).

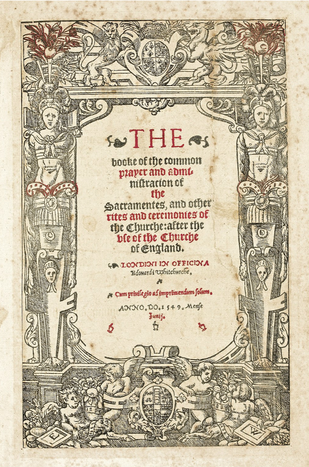

Augustine’s Preached Theology is the latest work from J. Patout Burns, emeritus professor of Catholic studies at Vanderbilt University Divinity School. An eminent patristics scholar with a particular focus on the North African church fathers, Burns’ other works include Cyprian the Bishop (2001) and Christianity in Roman North Africa (2014). In Burns’ own words, “This volume has been designed as a resource for identifying and studying Augustine’s theology as it was developed in his preaching” (p. 4). Though Burns occasionally refers to Augustine’s other theological works, this survey of Augustine’s theology is built uniquely from the corpus of his surviving sermons. Following a brief introduction about how to access Augustine’s sermons in critical editions as well as English, Burns focuses the first chapter on Augustine’s approach to interpreting Scripture. Though some space is given to Augustine’s allegorical readings, Burns especially emphasizes how Augustine read Scripture Christologically. In chapter 2, Burns discusses how Augustine preached about wealth and poverty. In his sermons, Augustine offers principles from Scripture for the wealthy, the poor, and those in between. He challenges all of them to be generous and to give alms. In chapter 3, Burns surveys Augustine’s preached thought on sin and forgiveness. He probes Augustine’s theological work against the Donatists who believed that forgiveness of sin was based on the holiness of their bishop. In chapters 4-7, Burns explores a bit of Augustine’s sacramental theology. In chapter 4, he surveys Augustine’s theology of baptism, which was also clarified in the face of the Donatist controversy. In chapter 5, Burns presents Augustine’s eucharistic theology, including some of his preached thought from John’s Gospel, particularly the bread of life passages. In chapter 6, he discusses Augustine’s teaching on marriage. Though Augustine chose celibacy and a monastic vocation, he taught that marriage was good, but that sexual intercourse was only for the purpose of procreation. In chapter 7, Burns probes Augustine’s thought on holy orders and the work of ordained ministers, which including shepherding and overseeing the people, preaching, and administering the sacraments. In chapter 8, Burns looks at Augustine’s understanding of Christ’s saving work. He discusses Augustine’s theology of the atonement and the extent of Christ’s death, burial, resurrection, and ascension. In chapter 9, Burns maps Augustine’s theological anthropology, especially in response to the Pelagian controversy. Burns clarifies Augustine’s thought on original sin and mankind’s inherited guilt from Adam and Eve. In the final chapter, Burns surveys more Christology, particularly the unity of Christ’s divine and human nature and Christ’s union with the church. Burn’s work has many strengths. First, it is evident that he has spent many years working through Augustine’s surviving corpus of sermons. Burns’ study offers scholars and students a starting place to explore more deeply any one of Augustine’s theological ideas that emerge from his preaching. Second, Burns rightly situates Augustine the theologian within the life and vocation of Augustine the preacher. Indeed, Augustine’s day job for the last forty years of his life was pastoring the church at Hippo and influencing the broader church in North Africa and the Roman world. Burns shows that Augustine’s preached theology was occasional. In one sense, his theology emerged simply from the biblical texts given to him because he preached from the lectionary and followed the church year. That said, Augustine also preached contextually and, at times, used his cathedra to address theological matters facing the church—most notably Donatist and Pelagian ideas. Again, Augustine was a shepherd who cared for and protected his flock as bishop and preacher. Third, Burns does a great job of teasing out Augustine’s doctrine of the Holy Spirit. Particularly, in responding to the Donatists who believed that the sacraments were effective because of the priest’s holiness, Augustine argues that they are effective because of the work of the Holy Spirit within the believer. Augustine’s Holy Spirit theology becomes clarified between reading and preaching Scripture in a context where there are challenges to orthodox teachings on the work of salvation. I only have one quibble with the book. While Burns does an excellent job in chapter 2 surveying Augustine’s preached thought on wealth and poverty, apart from a few paragraphs (p. 32), Burns fails to convey that Augustine was a monk who had taken a vow of poverty and simplicity. Though Augustine’s people had jobs and money, and he did not require that they embrace monastic simplicity, Burns still seems to underemphasize this contextual reality that the bishop of Hippo was also a monk who had embraced poverty. I am grateful to have read Burns’ latest work. I think it will serve students and scholars of Augustine, early North African and Latin Christianity, as well as those interested in homiletics and theological preaching.  On March 17, U2 released Songs of Surrender—40 songs from their catalog that were stripped down and delivered largely through vocals, acoustic guitar, and some piano. A product of U2’s democracy, each band member chose 10 songs to go on the album. While most of the selections were classic U2 songs, nearly one-fourth of the songs came from their most recent albums and single releases. Though one reviewer described the album as U2 covering themselves, Songs of Surrender is more of a reimagination of past songs. In some cases (Beautiful Day and Walk On), they’ve rewritten lyrics to reflect convictions for a new day. In some songs, such as Pride in the Name of Love, we distinctly hear a 60-something Bono singing with his 20-something self. In this sense, Songs of Surrender reminds me of St. Augustine’s work (along with his disciple Possidius) to create an index (indiculus) of his works toward the end of his life. While preparing the index, Augustine also wrote a new work called Reconsiderations (Retractationes), where he communicated how his thoughts had developed and how he had even changed his mind on some theological matters. It is a rare and wise feat to reflect on one’s life work. St. Augustine did it, and I think U2 is also doing it through Songs of Surrender. By stripping the songs down to vocals and an acoustic guitar, we hear more clearly the genius and beauty of the lyrics. And surprisingly, in many cases, the Edge captures the fullness of the songs with just an acoustic guitar. I found this to be particularly true in their interpretation of Bad, Out of Control, and Who’s Gonna Ride Your Wild Horses. The band has actually been playing acoustic versions of their songs in concerts for years. Over time, the acoustic form became the only way that songs like Stay (Far Away, So Close), Stuck in a Moment, Staring at the Sun, and Every Breaking Wave were performed live. The Songs of Surrender compilation is a busk of sorts. Within the past several years, U2 busked in the New York City and Berlin subway stations. In May 2022, just months after the Russian invasion of Ukraine, Bono and Edge played an acoustic concert before a small crowd in the Kyiv metro station. And recently, they played some of Songs of Surrender live on NPR’s Tiny Desk. Through these outings, U2 has shown they can play to an intimate audience of 60-80 just as well as a sold-out stadium of 60,000 to 80,000. While I’ve generally enjoyed listening to U2 dialogue with its past through this project, some of the songs were quite a bust for me. Where the Streets Have No Name (performed completely acapella!) and I Still Haven’t Found What I’m Looking For were just not big enough. For both songs, I needed the full band, a sound system, and a stadium of at least 50,000 people to make it work. It looks like they tried to play With or Without You without a bass guitar, which for me, is the instrument that supports and forms the whole song. Stay (Far Away, So Close) was also a disappointment. I wish they had gone with the already refined live acoustic version they’ve been playing for years. But U2 are always risk-takers. For me, the best song on Songs of Surrender (and my favorite all-time U2 song) was Walk On. It was originally written as a tribute to Aung San Suu Kyi, who won the Nobel Peace Prize from prison in 1991 for her efforts to advance democracy and freedom in her native Myanmar. Later, the band sang Walk On to memorialize the victims of September 11, 2001. In the Songs of Surrender version of Walk On, which included some new lyrics, they celebrate the courageous leadership of comedian turned-president Volodymyr Zelenskyy and the people of Ukraine in their struggle for freedom against the Russian invasion that began in March 2022. Songs of Surrender is a reimagination of 40 U2 songs. The record begins with One, their greatest hit from the 1990s and a testimony to their unity as a band all these years. It ends with 40, their version of Psalm 40, and a prayer that they closed many concerts with during the 1980s and again in parts of the 2000s. I like much of this album. And it makes me want to buy a ticket and get to the next available live U2 show. During orientation for a retreat a few years ago at Mepkin Abbey, a Benedictine monastery in the low country of South Carolina, I was initially surprised when the spiritual director said that the focal point of their community’s worship life was singing the Psalms. Though their daily worship, particularly within the eight daily offices, includes the reading and teaching of Holy Scripture, communal and personal prayer, lectio divina, confession of sin, and participating in the Holy Eucharist, chanting the Psalms (the entire Psalter every week) remains the center of worship (Rule of Benedict 18.23). In this brief reflection, I discuss how the Benedictine emphasis on chanting the Psalms harnesses a poetic and religious imagination toward the spiritual formation of the community. By first discussing how the Benedictine monks chant, I suggest that the habit of singing the Psalter provides an authentic apprenticeship in prayer that engages the auditory senses and a full range of emotions, forms the spiritual memory of the worshiper, and becomes a pathway to silence.

St. Benedict and Psalmody In several chapters in his Rule (8-9, 17-19, 42, 45), St. Benedict (480-547) gives instructions for psalmody in daily worship. In terms of style, Benedictine psalmody resembled an early form of plainsong later associated with Gregory the Great (ca. 540-604). Georg Holzherr (2016, 218) writes: The Rule recognizes not only the simple chanting of the Psalms, which in this case are sung without interruption, but also the customary chanting of the Psalms with antiphons. In the latter case one or more leader chanters sang the psalm while others present responded or end the psalm with the refrain “Amen” or “Alleluia.” Emphasizing that he and his monks stood continually in God’s presence, Benedict admonished the community: “let us stand to sing the Psalms in such a way that our minds are in harmony with our voices” (RB 19.7 in Holzherr 2016, 218). Undergirded by this heart of worship, the monks were to be serious, reverent, and attentive to psalmody. Sloppiness was not tolerated (RB 45). Authentic Prayer Engaging the Senses The Benedictine practice of chanting the Psalter is an authentic expression of prayer that engages the senses and emotions. This is particularly meaningful in a day when these values are often missing in Protestant worship. Dana Gioia (2022) warns: “Christianity has survived into the twenty-first century, but it has not come through unscathed. It has kept its head and its heart—the clarity of its beliefs and its compassionate mission. The problem is that it has lost its senses, all five of them.” One of the downsides of the Protestant Reformation was that worship and discipleship became much more textual, which diminished the place of the senses and imagination. Stratford Caldecott challenges this reality by stating, “The function of our senses is to enable beauty to penetrate within” (2017, 40). The beautiful theology of the Psalms ought to shape and form us in Christ as we sing (and hear) them in beautiful arrangements. In his reflection on Benedictine psalmody, Pope Benedict XVI (2008) captures this notion of beauty in prayer by reminding us that for St. Benedict, to pray and chant the Psalms was to sing with the angels. He writes: In the presence of the angels, I will sing your praise (cf. 138:1)—are the decisive rule governing the prayer and chant of the monks. What this expresses is the awareness that in communal prayer one is singing in the presence of the entire heavenly court, and is thereby measured according to the very highest standards: that one is praying and singing in such a way as to harmonize with the music of the noble spirits who were considered the originators of the harmony of the cosmos, the music of the spheres. We respond to God and his attributes (e.g., creation, glory, goodness, salvation, love) by praying and singing beautifully. Pope Benedict (2088) adds: “It shows that the culture of singing is also the culture of being, and that the monks have to pray and sing in a manner commensurate with the grandeur of the word handed down to them, with its claim on true beauty.” In addition to engaging all of our senses through psalmody, we are also invited to express a full range of emotions. The Psalms teach us to lament, rejoice, cry out to God in desperation, and celebrate. They invite us to be fully human in prayer—honest, raw, and broken. The Psalms challenge the repertoire of happy, “best life now” worship songs sung in many churches in North America today. Finally, the Psalms are a model for prayer. Because of their structure, they can be memorized as said or chanted prayers. When our Lord’s disciples asked him to teach them to pray (Luke 11:1), he could have easily responded that they could pray using the Psalter. Jesus referred to or quoted the Psalms repeatedly in his earthly ministry (Morales 2011). Memory Praying and chanting the Psalms helps us cultivate a memory of God’s work and faithfulness in our lives. Discussing the connection between language and memory, Rowan Williams writes, “Languages . . . chime with longing; as memory chimes with the totality of things” (2014, 133). Given that we make sense of our world within the parameters of language, poetic language and devices (what we find in the Psalms) help shape our being and our memory (William 2014, 132). That is, in the beauty of words and their creative and clever rhetorical ordering, we develop a deep connection to the memories and milestones in our lives. The Psalms were Israel’s playlist. A number of the Psalms are historic in nature (Pss 78, 105-107, 114, 135-136). Through them, the Israelites remembered God’s deliverance through the Exodus, his mighty saving acts, and other milestones in their journey to the Promised Land and toward being the people of God. Like Israel, we are a forgetful people, and we fail to remember God’s goodness, presence, and saving ways. Regularly praying and chanting the Psalms allows us to enlarge our memory of God’s work in our lives. Though the Psalms recount God’s work in Israel, in our meditation and prayers, we can build our memory of God’s presence and faithfulness, too. The structure and poetic devices of the Psalms provide a great house for us to remember God. Silence Finally, psalmody in the Benedictine tradition naturally leads us to silence and rest. Benedict’s direction for Compline (nighttime prayer) was simple: “Compline is limited to three Psalms, which are sung straight through without adding an antiphon. After the psalmody come the hymn for this hour, followed by a reading, a versicle, ‘Lord have mercy,’ a blessing and a dismissal” (RB 17.9 in Holzherr, 2016, 207). Benedict was also strict about the contemplative and quiet manner in which monks should depart the nighttime office. He adds: “On leaving Compline, no one will be permitted to speak further. If anyone is found to transgress this rule of silence, he must be subjected to severe punishment” (RB 42.8-9 in Holzherr 2016, 336). The grand silence after Compline was intended to lead the monks toward physical and spiritual rest. The appeal for rest resounds repeatedly in the collects and closing prayer in the Compline office: “Be present, O merciful God . . . so that we who are wearied by the changes and chances of this life may rest in your eternal changelessness . . . Keep watch, dear Lord, with those who work . . . give rest to the weary . . . guard us sleeping . . . and asleep we may rest in peace” (BCP 2019, 63-65). These prayers remind us of the Psalmist’s admonition to laborers to trust the Lord for his provision and to accept the necessary blessing of sleep: “in vain you rise early and stay up late, toiling for food to eat— for he grants sleep to those he loves” (Ps 127:2). By praying and chanting the Psalms, we remember God’s character and ways and cast all of our cares upon him. This leads us to physical and spiritual rest. Conclusion Following in the way of Benedict, the Psalms offer us a lifetime apprenticeship in the school of prayer. They teach us to lament and rejoice and to pray honestly as authentic human beings who are broken but hopeful about the journey to wholeness and flourishing. Through daily praying and meditating on the Psalms, we construct a memory of God’s faithfulness in our lives. Following Benedict’s admonitions for Compline, praying the Psalms at night (and during the day) leads us to a place of rest. While these are useful habits for Benedictine monks, they are also relevant and meaningful approaches to the Christian life for the people in my parish. Bibliography Benedict XVI. “Apostolic Journey of His Holiness Benedict XVI to France.” Online: https://www.vatican.va/content/benedict-xvi/en/speeches/2008/september/documents/hf_ben-xvi_spe_20080912_parigi-cultura.html. Book of Common Prayer (2019). Huntingdon Beach: Anglican House Media. Caldecott, Stratford. Beauty for Truth’s Sake: On the Re-enchantment of Education. Grand Rapids: Brazos, 2017. Gioia, Dana. “Christianity and Poetry.” First Things. Online: https://www.firstthings.com/article/2022/08/christianity-and-poetry Holzherr, Georg. The Rule of Benedict: An Invitation to the Christian Life. Collegeville: Liturgical Press, 2016. Morales, L. Michael. “Jesus and the Psalms.” Online: https://www.thegospelcoalition.org/article/jesus-and-the-psalms/. Williams, Rowan. The Edge of Words: God and the Habits of Language. London: Bloomsbury, 2014. I was really looking forward to getting my hands on The Apostles’ Creed for All God’s Children and it did not disappoint. With FatCat as our guide, the book and illustrations provide a wonderful teaching tool for children to engage the riches of the gospel. Ben Myers, who has already written a guide for adults on the Apostles’ Creed, takes each line of the creed and has written inviting and probing questions while also crafting a brief and hopeful summary for each line. He has written enough to invite good meditation and discussion with just the right amount of text. Natasha Kennedy’s FatCat font also facilitates the reading. The book concludes with a plan for daily family prayer as well as additional study resources for parents and others discipling children.

Though I am a novice at art appreciation, Natasha Kennedy’s illustrations have stoked my imagination, making a reflection on the creed more inviting. I like that Jesus has accurately been depicted as a person of color and the characters illustrated in the book are wonderfully diverse. I think just about any child in the world opening this book will see someone that looks like them; this work is for “all God’s children.” The artwork for the lesson on creation (“maker of heaven and earth”) was bright with the sun, sky, animals, and buildings, revealing the goodness of our creator. The birth of Christ (“who was conceived by the Holy Spirit, born of the Virgin Mary”) was depicted with an amazing purple background fitting for the King of Kings. The death of Christ (“was crucified, died, and was buried”) was appropriately dark and somber (but still purple), while the resurrection (“on the third day he rose again from the dead”) made me squint from the brightness. I could envision this book being used in family devotions and catechism over seventeen sessions (days or weeks). This is a great resource for a young family to be a little church. Like the Book of Common Prayer, it is a great tool for parents who may not have theological training to disciple their kids. I could see it also providing the framework for a semester-long Sunday school class for children. My only quibble is that the authors and publisher have chosen the older language of the creed—“he descended into hell”—instead of the more commonly used “he descended to the dead.” So this language will mostly likely be different from the creed said in most churches today. Also, using “hell” instead of “dead” might present some teaching challenges for parents and teachers. Despite this, the explanatory text is very helpful: “Where will I go when I die? Where do all the dead go? Where it is Jesus went there, too. He went down as far as we had fallen. He took death’s keys to free the captives. He overcame death with his life.” Some parents and teachers may just opt to say “He descended to the dead” for this lesson. In short, I love this book and want to slowly read it myself and take in the art and illustrations more. Though I have older teenagers, I’m tempted to read this to them at bedtime for the next seventeen days.  Pilgrimage (peregrinatio) has occupied a central place in Celtic Christianity and spirituality. For many Celtic monks, participating in pilgrimage was regarded as “the highest form of penance and self-renunciation.”[1] In a sermon, the famous missionary monk Columbanus (543-615) described the entire Christian life as a pilgrimage: We are travelers and pilgrims in this world . . . as guests of the world, free of lusts and earthly desires . . . let us fill our mind with heavenly and spiritual forms . . . turning our back on evil and laying aside all apathy, let us strive to please him who is everywhere, so that we may joyfully and with a good conscience pass over the road of this world to the blessed and eternal home of our eternal Father.[2] As Celtic monks pushed out on pilgrimage to the edges of the known world, they encountered the God of creation in worship and also put themselves in danger. Those who took to the sea on pilgrimage were known as “green martyrs.”[3] Many Celtic monks also became missionaries, leading pagans to Christ and planting new churches and monasteries along the way.[4] In this paper, I probe more deeply into the spirituality of pilgrimage by exploring the famous eighth-century hagiographical work, The Voyage of Brendan.[5] In particular, I discuss the rhythms of pilgrimage through daily worship and through the church year. I conclude by summarizing themes of Celtic pilgrimage that might also encourage pilgrims on the way today. Background on St. Brendan and The Voyage St. Brendan of Clonfert (484-577), also known as “the navigator,” was born in County Kerry in southwest Ireland. Remembered as one of the one of the Twelve Apostles (monastic saints) of the Irish church, Brendan founded the monastery at Clonfert in western Ireland.[6] Though Brendan imitated other Irish monks and traveled widely in pilgrimage and ministry, The Voyage of Brendan has never been regarded as an authentic historic account.[7] Rather, the story, a theological allegory, conveys the salvation journey of the Irish church as a whole with a focus on its ascetic values. The Voyage is about Brendan (and the pilgrim Irish church) going in search of the “Promised Land of the Saints.”[8] Brendan’s voyage to the Promised Land begins when he hears the testimony of the monk Barinthus, who had previously made the journey.[9] Though inspired and eager to push out to sea, Brendan first enters a period of discernment that included fasting, prayer, and seeking the counsel of his community. After, Brendan sets out on his own voyage with a community of fourteen monks. Sacred Time and Spiritual Rhythms Brendan’s journey takes a total of seven years where he and his community are met with obstacles and hardships at sea—a lack of wind, lack of food, demons, and sea monsters—before they reach the Promised Land and return home. This journey is framed by sacred time—spiritual rhythms shaped by both the daily office and the major feasts of the church year. The Daily Office. Let us first examine how Brendan’s journey is shaped by faithfulness to daily worship. After being at sea for an initial forty days and running out of food, Brendan and company are led to an island where they find a community of monks who feed them. Immediately after eating, all of the monks pray compline (nighttime) prayers. During the night, Brendan and one of his monks are attacked by a demon, which leads Brendan to spend the night in vigils. After the monk succumbs to temptation, Brendan leads him through the Eucharist as a means of confession and penance.[10] Arriving at another island where God has again provided for their physical needs, Brendan’s first action is to sing the daily office. Moving on to another island, they spend the night in prayer and vigils. The next day, Brendan directs each monk to pray their own individual masses. Once back in the boat, Brendan leads the community in mass.[11] Arriving at another island, they are welcomed by a community of monks into the refectory for a silent meal. Afterward, all of the monks enter the church and sing the nighttime office.[12] Emphasizing the community’s commitment to silence, the abbot tells Brendan that “it is only when we sing praise to God that we hear a human voice.”[13] Here, it seems that Brendan’s monastic vision is being enlarged by the community’s vow of silence. On two additional days of the journey, Brendan and his monks are remembered praying each of the daily offices, including nighttime vigils, terce, sext, vespers, and compline. These days are completely organized around the office. The appointed Psalms are especially highlighted.[14] With the exception of Brendan leading the community in mass aboard the boat, every other instance of daily worship takes place on an island where they have found nourishment, rest, and refuge from the dangers of the sea. In The Voyage, the daily office seems to represent daily withdrawal from the world where believers find refuge, nourishment, and rest in God. Green martyrs are sustained by faithful worship. The Church Year. In addition to daily worship, Brendan’s voyage was framed by the major feasts of the church year. In the first year of the voyage, they arrive at one island on Maundy Thursday and stay through Holy Saturday. The monks also receive a lamb in order to celebrate the Feast of the Resurrection. From that island, they secure enough food to last them until Pentecost. At the end of the first year, they return to the same island—an island of birds—to celebrate Easter. The birds tell Brendan and his monks that the first year of their voyage was complete—starting and ending with Easter—and that six years remained until they reached the Promised Land.[15] At Easter the following year, they are met by someone who offers them enough provisions to last until Pentecost. From there, they learn that they will travel and reach another island by Christmas and that they will stay there through Epiphany.[16] Setting out again, they receive enough supplies to last them until Lent. They continue their journey to their usual island destination to celebrate Holy Week. Then they depart from the island on the same path with enough provisions to last them until Pentecost.[17] At the island of the birds, one of the birds summarized the circular pattern of Brendan’s seven-year voyage: God has appointed four places for you for each season of the year where you shall stay until seven years of your pilgrimage are over. You shall spend Maundy Thursday with your steward who is there each year, the Easter vigil on the back of a whale, the Feast of Easter until the octave of Pentecost with us, and the Nativity of the Lord with the community of Ailbe. At the end of seven years, after great trials of various kinds, you will find the Promised Land of the Saints which you seek and there you shall live for forty days before God shall lead you back to the land of your birth.[18] At last, Brendan and the monks reach the Promised Land of Saints. They are told: “This is the land which you have sought for so long. You were not able to find it immediately because God wished to show you many of his wonders in the ocean.”[19] Having reached their destination, Brendan and his community return home and Brendan dies shortly thereafter. Conclusion What do we learn about Celtic spiritual pilgrimage in The Voyage? First, Celtic Christians and monks became impassioned to imitate the examples of those who had gone on pilgrimage before. Brendan was inspired by the example of Barinthus. This account resembles St. Augustine of Hippo’s (354-430) conversion to Christ and the ascetic life after he learned of the example of St. Antony in Egypt.[20] Second, Brendan’s story emphasizes discernment about the call to the ascetic life. After hearing Barinthus’ testimony, Brendan takes time to fast and pray and seek the counsel of his community. The Voyage teaches us that the ascetic life should not be entered into lightly or alone. Third, in Brendan’s pilgrimage—a difficult journey—God provides for their needs along the way. Like St. Paul, Brendan and his community relied on the hospitality of people (monastic communities in his case) to provide for his needs.[21] Fourth, the seven-year journey is characterized by faithfulness in daily worship. In almost every case, Brendan and his community land on an island, are refreshed by food, rest, and hospitality, and then they pray the daily offices. A remarkable parallel exists between physical nourishment and rest and spiritual nourishment and rest. Tom O’Loughlin notes that The Voyage presents a community of monks growing in their liturgical practice until their worship is perfected in the Promised Land of Saints.[22] Finally, their circular “map” to the Promised Land is comprised of the major feasts on the church calendar. Each feast offered them nourishment, rest, and renewal needed to continue the arduous voyage. In the midst of their voyage, they could also look forward to the next feast on the calendar to keep them going. While the feast day pattern was revealed feast by feast in the first year, in the six years that followed, the rhythm was revealed to them and they knew what to expect. As the rhythms of the church year became ingrained in them, they grew in their faith and became mature pilgrims.[23] While The Voyage of Brendan is an allegory of the medieval Irish church’s salvation journey, the spiritual truths presented in these five summary points can serve as a guide to Christian pilgrims today. We embark on the life of faith in part because of the examples of others. We do it in community with others. We recognize that following Christ is a spiritual battle. Finally, we must develop spiritual rhythms around daily worship and the church year in order to stay faithful on our spiritual journeys. [1] Edward L. Smither, Missionary Monks: An Introduction to the History and Theology of Missionary Monasticism (Eugene: Cascade, 2016), 25. See further Marilyn Dunn, The Emergence of Monasticism: From the Desert Fathers to the Middle Ages (Oxford: Blackwell, 2003), 140, 149-150; also Elva Johnston, “The Voyage of Saint Brendan: Landscape and Paradise in Early Medieval.” Brathair 19 no. 1 (2019): 38. [2] Columbanus, Sermon 8 in Oliver Davies and Thomas O’Loughin, eds. Celtic Spirituality (New York: Paulist, 1999), 356. [3] John E. Lawyer, “Three Celtic Voyages: Brendan, Lewis, and Beuchner.” Anglican Theological Review 84 no. 2 (2002): 322. [4] See further Smither, Missionary Monks, 64-81. [5] See further Johnston, “The Voyage of Saint Brendan,” 36. [6] St. Brendan the Navigator (web site). Online: http://www.saint-brendan.org/history.asp (accessed November 23, 2020). [7] See further Ted Olsen, Christianity and the Celts (Downers Grove: Intervarsity, 2003), 125. [8] Davies and O’Loughlin, Celtic Spirituality, 34; see also Lawyer, “Three Celtic Voyages,” 321. [9] The Voyage of Brendan in Davies and O’Loughlin, Celtic Spirituality, 155-158. All subsequent references to The Voyage are taken from Davies and O’Loughlin. [10] The Voyage of Brendan, 159-161. [11] The Voyage of Brendan, 161-163. [12] The Voyage of Brendan, 168-170. [13] The Voyage of Brendan, 170. [14] The Voyage of Brendan, 163-164, 170; see further Johnston, “The Voyage of Saint Brendan,” 44; also Lawyer, “Three Celtic Voyages,” 324. [15] The Voyage of Brendan, 161-165. [16] The Voyage of Brendan, 166-167. [17] The Voyage of Brendan, 171-173. [18] The Voyage of Brendan, 174. [19] The Voyage of Brendan, 189. [20] See Augustine, Confessions 8.14. [21] See further Acts 16:13, 21:4–8, 28:14; Rom 12:13. [22] See further Thomas O’Loughlin, Journeys on the Edges: The Celtic Tradition (London: Darton, Longman, Todd, 2000), 93-95. [23] See further O’Loughlin, Journeys on the Edges, 95-97.  Vince L. Bantu. A Multitude of All Peoples: Engaging Ancient Christianity’s Global Identity. Downers Grove: IVP Academic, 2020. xi + 239pp. $35.00 paperback. “Christianity is and always has been a global religion . . . it is important to never to think of Christianity as becoming global” (1). Vince Bantu opens his work with this claim and supports it with a thorough survey of the early non-western church Following this introduction, Bantu devotes chapter 1 to the origins of western church dominance following the emergence of the Emperor Constantine (d. 337) and the Council of Chalcedon of 451. Employing Hellenistic language on the two natures of Christ, the formula of Chalcedon succeeded in alienating African and eastern churches—communities that possessed an orthodox Christology but used different vocabulary to express it. In chapter 2, Bantu describes the churches of Africa (Nubia, Egypt, Ethiopia, North Africa), while in chapter 3 he presents Christians of the Middle East (Syria, Lebanon, Arabia, Armenia, Georgia). In chapter 4, Bantu focuses on the Church of the East in Syria and Persia and mission along the Silk Road through Central Asia to China. In a brief concluding chapter, he argues that the present global church should celebrate contextual theology and set apart indigenous leaders to remain truly global. While Bantu’s thesis does not break new ground on early Christianity’s global nature, his work strongly supports the works of Phillip Jenkins, Scott Sunquist, Dale Irvin and others by providing a robust picture of ancient African, Middle Eastern, and Asian Christianity. I especially appreciated the section on St. Ephrem the Syrian whose theological method and products included hymns and (madrashe) and homilies (memre)—a form that developed from and resonated with his Syrio-Persian context. A few years ago, I was at a theology conference where a western theologian discounted St. Ephrem’s works as real theology because he did not write in prose. That theologian needs this book. Though Bantu argues that western cultural and theological hegemony characterizes the global church’s story, this is not the whole story. To be sure, Byzantine church and political leaders pressured and even oppressed those who rejected Chalcedon. However, as Bantu shows (132-136), some myaphysite churches in the Middle East also oppressed their fellow Melkite Christians, who followed Chalcedon. Sadly, the Egyptian Coptic Abba Shenoute used violence against pagans and one wayward monk in his African context (17). Catholicos Timothy of Baghdad certainly navigated nasty church politics within the Church of the East. Having done my graduate work on North African Christianity, I was happy to see Bantu’s survey of the African church in chapter 2. While the African fathers discussed (Tertullian, Cyprian, Augustine) were indeed African, they were also culturally Roman. Tertullian and Augustine lived for a period in Italy and there is no evidence that any of these fathers knew a language other than Latin or Greek. It would have been good to recognize that North Africa, particularly the cities, was really Roman Africa. In summary, Vince Bantu has done an excellent job of telling the story of the non-western church in the ancient world and certainly supported his claim for an early global Christianity. This work should be read by professors and students of church and mission history as well as those currently serving in ministry in Africa, the Middle East, and Asia. For Further Reading Jenkins, Phillip. The Lost History of Christianity: The Thousand Year Golden Age of the Church in the Middle East, Africa, and Asia and How it Died. New York: HarperOne, 2009. Irvin, Dale T. and Sunquist, Scott W. and History of the World Christian Movement: Earliest Chrisitanity to 1453. Maryknoll: Orbis, 2001. Ott, Craig and Netland, Harold. Globalizing Theology: Beliefs and Practice in an Era of World Christianity. Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2006.  This weekend at the Southeast Evangelical Missiological Society meeting, I will present the following paper: Communicating catholic and Indigenous Christianity: The Book of Common Prayer’s Contribution to Global Mission. Below is a brief abstract: When Thomas Cranmer (1489-1556) published the first Book of Common Prayer (BCP) in 1549, he offered a means for the English church to be liturgically catholic and culturally English. That is, the prayer book provided continuity for the whole (catholic) English church for daily prayer, weekly worship, Scripture reading, celebrating the sacraments, and following the major feasts of the church year. Because the BCP was produced in the English vernacular, the prayer book also allowed them to be fully English in their worship life. As the Anglican church began to participate in global mission in the early eighteenth century, the prayer book continued to be a means of encouraging orthodoxy and catholicity while also promoting indigenous Christianity. Following a brief history and theology of the BCP, I will support this claim by exploring Anglican mission practice in South India and New Zealand and the development of the prayer book in those contexts. I conclude with a brief missiological reflection on the place of a tool such as the prayer book for communicating the gospel and making disciples among all peoples today. Read an entire draft of the paper HERE.  Kevin Ward, A History of Global Anglicanism (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006). Pp. xi + 356. ISBN: 978-0-521-00866-2; $63.99 paperback. A History of Global Anglicanism is a 2006 work from Professor Kevin Ward, who served as Senior Lecturer in African Studies at the University of Leeds (UK) until his retirement in 2014. In addition to being a prolific scholar in the fields of World Christianity, African Christianity and the history of mission in Africa, Ward is a priest in the Church of England and a trustee of the Church Missionary Society (CMS). In a well-researched and well written work, Ward’s stated aim is to “write a history of the Anglican communion from its inception as a worldwide faith, at the time of the Reformation, to the present day” (p. 1). In his introductory chapter entitled “Not English, but Anglican,” Ward adds that he will emphasize the “activities of the indigenous peoples of Asia and Africa, Oceana and America in creating and shaping the Anglican communion” (p. 1). Though Ward acknowledges that it is impossible to tell the global Anglican story apart from British colonial history, and he discusses the work of western Anglican missionaries, he aims to narrate the story of non-English global Anglicanism—those who now comprise the vast majority of the global Anglican communion. In this review, my aim is to evaluate Ward’s work by first presenting his main arguments in support of his thesis and then discussing the strengths and weaknesses of his work. Following his introductory chapter, Ward develops his thesis by first discussing non-English Anglicanism in the British Isles—in Wales, Ireland, and Scotland (chapter 2). In chapter 3, he describes how Anglicanism became an influential church (Episcopal Church USA) but not a state church in the highly democratic United States. In the following chapter, the author discusses Canadian Anglicanism, focusing largely on the experience of First Nations (indigenous) peoples (chapter 4). Next, Ward narrates Anglican history in the Caribbean (chapter 5), a story that cannot be told apart from the painful legacy of slavery. In chapter 6, he briefly describes Latin American Anglicanism, one of the smallest parts of the global Anglican communion and one that was not touched by British colonialism. In chapters 7-9, he draws upon a career of research and ably surveys the Anglican church in Africa (West, Southern, and East) with emphasis on some of the largest Anglican communions in the world (Nigeria, Uganda, Kenya). Following a brief chapter on Anglican mission and presence in the Middle East (chapter 10), Ward probes the fascinating account of Anglicanism in South Asia (chapter 11) with emphasis on the former British colony, India. In chapters 12-13, he presents the small Anglican communion in China and the Asian Pacific. Ward concludes by narrating Anglican history in Oceania (chapter 14), focusing mostly on Australia and New Zealand. The author does not spare the reader the painful way in which British Anglicans treated Aboriginal peoples. In a final summary chapter (chapter 15), Ward recaps his thesis with some discussion on the problems facing 21st century global Anglicanism, especially disagreements over the ordination of women and homosexuality. Among the many strengths of Ward’s work, I will focus on three areas. First, while I expected to encounter a non-English global Anglicanism in his chapters on Latin America, Africa, and Asia, I found that Ward succeeded in presenting a globally Anglican church in his chapter on the British Isles (chapter 2). With diminishing support from the crown, and lacking the stature of being a state church, the Anglican church developed and even flourished—to the point of sending out global missionaries—in predominantly Roman Catholic Ireland and Presbyterian Scotland. Ward argues his thesis quite well by surveying the Anglican story in the non-English portion of the British Isles, which sets the tone for the character of global Anglicanism. Second, Ward teases out well the tension between catholicity and local expressions of church. On one hand, global Anglicans in the USA, India, and Japan among others have been united by a Prayer Book tradition and what was articulated as the Lambeth Quadrilateral (Scripture, creeds, sacraments, historic episcopate). In many parts of the global communion, particularly those from communal and collectivist societies (e.g. India, Africa, Latin America), national churches have valued belonging to the historic and global Christian community. On the other hand, Anglicans in China, India, and parts of Africa have valued developing the local identity of the church. Desiring unity, Indian Anglicans joined with other denominations to launch the Church of South India (pp. 235-237, 307) while in China, the Holy Catholic Church of China was formed (p. 252). In many parts of Africa, the Anglican liturgy is an exuberant African experience with locally developed hymns and dance. Finally, through this survey Ward does a good job of showing the diversity within the global Anglican communion. Such diversity certainly includes the distinction between colonial and settler churches and indigenous churches (e.g. the settler church and Maori fellowship in New Zealand). It also includes the various missionary groups, including the high church oriented SPCK and SPG, the more evangelically oriented CMS, as well as later missionary movements from the Episcopal Church USA and the Anglican Church of Canada. The missionary elements of global Anglicanism have been very diverse. In addition to these affirming critiques, I do have some quibbles. First, while I understand that a book of this scale requires some difficult organizational decisions, I fail to grasp how Sudan is listed in the Middle East section (pp. 205-211). Though the Episcopal Church of Sudan has a historic diocesan relationship with Egypt, Sudanese Anglicans, who largely inhabit the southern portion of the country, are not Middle Eastern Arabs. Culturally, they have a much stronger affinity with other East African peoples and the church was nurtured historically by the East African revivals (p. 208). In 2011, the peoples of the south seceded to form the Republic of South Sudan. Second, Ward could have emphasized more the work of three significant Anglican mission leaders. Roland Allen (1868-1947), the Tractarian influenced SPG church planter in China and Kenya, was only mentioned briefly (pp. 249, 273). While Ward rightly points out the innovative three-self missiological thought (self-supporting, self-led, self-propagating) of CMS leader, Henry Venn (pp. 35-37, 116-119, 300), Allen actually implemented these ideas in the Chinese context while highlighting afresh St. Paul’s missiology of church planting. Similarly, much more discussion could have been given to Bishop Kenneth Cragg’s (1913-2012) work in the Middle East (pp. 201-202, 211-212). A Quranic scholar highly respected by Muslim theologians, Cragg’s approach to dialogue with Muslims introduced a significant paradigm shift for mission to Muslims in the twentieth century. Finally, Ward does not even mention the contributions of Anglican missionary theologian John Stott (1921-2011). An organizer of the 1974 Lausanne Congress on World Evangelization, Stott became an architect of global missiology by inviting partnership and input from non-western theologians, especially Latin Americans, in crafting the Lausanne Covenant. Third, while Ward often celebrates the theological diversity and various expressions within global Anglicanism, he refers negatively to some groups, especially Pentecostals (p. 100) and the Anglican Diocese of Sydney in Australia (pp. 13, 284-286, 295, 314). The Sydney Diocese is characterized by Reformed, Evangelical, and even charismatic qualities. Since these streams of Christian theology and conviction have been welcomed within the historic Anglican communion, I fail to grasp Ward’s apparent intolerance for this group of Australian Anglicans. Finally, while debates about women in ministry and human sexuality have certainly divided Anglicans over the last several decades, Ward’s concluding chapter (“escaping the Anglo-Saxon captivity of the church?”) seemed overly focused on the homosexuality debate. In this final chapter, he aims to sketch out the present and future of global Anglicanism but in the end, he seems to get stuck on this one issue. While this is no small matter and it will require the prayer, discernment, and biblical reflection of the global church, the global Anglican communion has many other problems, and the church should not be defined by this one issue. Critiques aside, Ward succeeds in presenting a thorough study on global Anglicanism beyond the English context. This work will continue to be a rich resource for clergy, missionaries, and Anglicans around the world. For students of global Christianity, the individual chapters of this book offer excellent starting points for deeper research on the regions in question. Since Ward’s book appeared in 2006, global Anglicanism has continued to evolve so this work provides a foundation for continued study. |

Archives

November 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed