posts

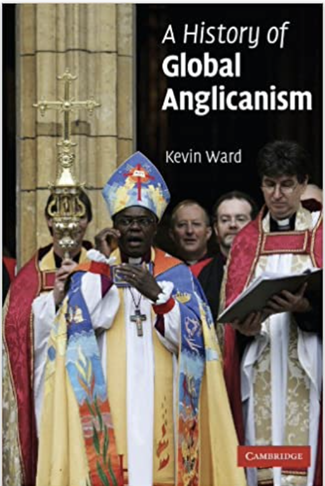

Kevin Ward, A History of Global Anglicanism (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006). Pp. xi + 356. ISBN: 978-0-521-00866-2; $63.99 paperback. A History of Global Anglicanism is a 2006 work from Professor Kevin Ward, who served as Senior Lecturer in African Studies at the University of Leeds (UK) until his retirement in 2014. In addition to being a prolific scholar in the fields of World Christianity, African Christianity and the history of mission in Africa, Ward is a priest in the Church of England and a trustee of the Church Missionary Society (CMS). In a well-researched and well written work, Ward’s stated aim is to “write a history of the Anglican communion from its inception as a worldwide faith, at the time of the Reformation, to the present day” (p. 1). In his introductory chapter entitled “Not English, but Anglican,” Ward adds that he will emphasize the “activities of the indigenous peoples of Asia and Africa, Oceana and America in creating and shaping the Anglican communion” (p. 1). Though Ward acknowledges that it is impossible to tell the global Anglican story apart from British colonial history, and he discusses the work of western Anglican missionaries, he aims to narrate the story of non-English global Anglicanism—those who now comprise the vast majority of the global Anglican communion. In this review, my aim is to evaluate Ward’s work by first presenting his main arguments in support of his thesis and then discussing the strengths and weaknesses of his work. Following his introductory chapter, Ward develops his thesis by first discussing non-English Anglicanism in the British Isles—in Wales, Ireland, and Scotland (chapter 2). In chapter 3, he describes how Anglicanism became an influential church (Episcopal Church USA) but not a state church in the highly democratic United States. In the following chapter, the author discusses Canadian Anglicanism, focusing largely on the experience of First Nations (indigenous) peoples (chapter 4). Next, Ward narrates Anglican history in the Caribbean (chapter 5), a story that cannot be told apart from the painful legacy of slavery. In chapter 6, he briefly describes Latin American Anglicanism, one of the smallest parts of the global Anglican communion and one that was not touched by British colonialism. In chapters 7-9, he draws upon a career of research and ably surveys the Anglican church in Africa (West, Southern, and East) with emphasis on some of the largest Anglican communions in the world (Nigeria, Uganda, Kenya). Following a brief chapter on Anglican mission and presence in the Middle East (chapter 10), Ward probes the fascinating account of Anglicanism in South Asia (chapter 11) with emphasis on the former British colony, India. In chapters 12-13, he presents the small Anglican communion in China and the Asian Pacific. Ward concludes by narrating Anglican history in Oceania (chapter 14), focusing mostly on Australia and New Zealand. The author does not spare the reader the painful way in which British Anglicans treated Aboriginal peoples. In a final summary chapter (chapter 15), Ward recaps his thesis with some discussion on the problems facing 21st century global Anglicanism, especially disagreements over the ordination of women and homosexuality. Among the many strengths of Ward’s work, I will focus on three areas. First, while I expected to encounter a non-English global Anglicanism in his chapters on Latin America, Africa, and Asia, I found that Ward succeeded in presenting a globally Anglican church in his chapter on the British Isles (chapter 2). With diminishing support from the crown, and lacking the stature of being a state church, the Anglican church developed and even flourished—to the point of sending out global missionaries—in predominantly Roman Catholic Ireland and Presbyterian Scotland. Ward argues his thesis quite well by surveying the Anglican story in the non-English portion of the British Isles, which sets the tone for the character of global Anglicanism. Second, Ward teases out well the tension between catholicity and local expressions of church. On one hand, global Anglicans in the USA, India, and Japan among others have been united by a Prayer Book tradition and what was articulated as the Lambeth Quadrilateral (Scripture, creeds, sacraments, historic episcopate). In many parts of the global communion, particularly those from communal and collectivist societies (e.g. India, Africa, Latin America), national churches have valued belonging to the historic and global Christian community. On the other hand, Anglicans in China, India, and parts of Africa have valued developing the local identity of the church. Desiring unity, Indian Anglicans joined with other denominations to launch the Church of South India (pp. 235-237, 307) while in China, the Holy Catholic Church of China was formed (p. 252). In many parts of Africa, the Anglican liturgy is an exuberant African experience with locally developed hymns and dance. Finally, through this survey Ward does a good job of showing the diversity within the global Anglican communion. Such diversity certainly includes the distinction between colonial and settler churches and indigenous churches (e.g. the settler church and Maori fellowship in New Zealand). It also includes the various missionary groups, including the high church oriented SPCK and SPG, the more evangelically oriented CMS, as well as later missionary movements from the Episcopal Church USA and the Anglican Church of Canada. The missionary elements of global Anglicanism have been very diverse. In addition to these affirming critiques, I do have some quibbles. First, while I understand that a book of this scale requires some difficult organizational decisions, I fail to grasp how Sudan is listed in the Middle East section (pp. 205-211). Though the Episcopal Church of Sudan has a historic diocesan relationship with Egypt, Sudanese Anglicans, who largely inhabit the southern portion of the country, are not Middle Eastern Arabs. Culturally, they have a much stronger affinity with other East African peoples and the church was nurtured historically by the East African revivals (p. 208). In 2011, the peoples of the south seceded to form the Republic of South Sudan. Second, Ward could have emphasized more the work of three significant Anglican mission leaders. Roland Allen (1868-1947), the Tractarian influenced SPG church planter in China and Kenya, was only mentioned briefly (pp. 249, 273). While Ward rightly points out the innovative three-self missiological thought (self-supporting, self-led, self-propagating) of CMS leader, Henry Venn (pp. 35-37, 116-119, 300), Allen actually implemented these ideas in the Chinese context while highlighting afresh St. Paul’s missiology of church planting. Similarly, much more discussion could have been given to Bishop Kenneth Cragg’s (1913-2012) work in the Middle East (pp. 201-202, 211-212). A Quranic scholar highly respected by Muslim theologians, Cragg’s approach to dialogue with Muslims introduced a significant paradigm shift for mission to Muslims in the twentieth century. Finally, Ward does not even mention the contributions of Anglican missionary theologian John Stott (1921-2011). An organizer of the 1974 Lausanne Congress on World Evangelization, Stott became an architect of global missiology by inviting partnership and input from non-western theologians, especially Latin Americans, in crafting the Lausanne Covenant. Third, while Ward often celebrates the theological diversity and various expressions within global Anglicanism, he refers negatively to some groups, especially Pentecostals (p. 100) and the Anglican Diocese of Sydney in Australia (pp. 13, 284-286, 295, 314). The Sydney Diocese is characterized by Reformed, Evangelical, and even charismatic qualities. Since these streams of Christian theology and conviction have been welcomed within the historic Anglican communion, I fail to grasp Ward’s apparent intolerance for this group of Australian Anglicans. Finally, while debates about women in ministry and human sexuality have certainly divided Anglicans over the last several decades, Ward’s concluding chapter (“escaping the Anglo-Saxon captivity of the church?”) seemed overly focused on the homosexuality debate. In this final chapter, he aims to sketch out the present and future of global Anglicanism but in the end, he seems to get stuck on this one issue. While this is no small matter and it will require the prayer, discernment, and biblical reflection of the global church, the global Anglican communion has many other problems, and the church should not be defined by this one issue. Critiques aside, Ward succeeds in presenting a thorough study on global Anglicanism beyond the English context. This work will continue to be a rich resource for clergy, missionaries, and Anglicans around the world. For students of global Christianity, the individual chapters of this book offer excellent starting points for deeper research on the regions in question. Since Ward’s book appeared in 2006, global Anglicanism has continued to evolve so this work provides a foundation for continued study. Comments are closed.

|

Archives

November 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed