posts

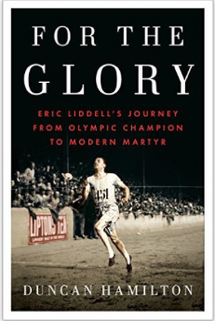

On and off this summer, I have been reading through Duncan Hamilton's biography of Eric Liddell, entitled For the Glory. Liddell, of course, won the gold medal in the 400 meters in the 1924 Paris Olympics and his story was featured in the film "Chariots of Fire." The focus of Hamilton's book is what happened after the Olympics; that Liddell returned to China where his parents had been serving with the London Missionary Society and after a number of years serving as a missionary among the Chinese, he died of a brain tumor in a Japanese controlled concentration camp in 1945. Though Liddell received a good theological education in Scotland before going to China, what struck me from his biography was how he grew as a theologian amid the hardships in China, especially as the Japanese began to control the country more and more. After Liddell's LMS mission station was closed by the Japanese in 1941, he was placed under house arrest and was forbidden from preaching, leading church services, and visiting Chinese believers. It is interesting how Liddell--someone who believed in laboring every minute of the day for God's glory--responded to these constraints. Hamilton writes: Liddell was always scribbling on pads and loose paper, where he put down thoughts and ideas or short quotations that inspired him. His advice to everyone was: "Take a pen and pencil and write down what comes to you." Liddell was widening his knowledge of theology and committing to memory those few books of the Bible he couldn't already quote (p. 247). So Liddell, who was already a divinity school graduate, a Bible teacher, preacher, and missionary, used this season of limited activity to reflect on Scripture in his context of hardship and to grow as a theologian. In the twenty-first century western world, theology is often articulated from the comfort of offices, libraries, and in the stimulating environments of professional societies. Similar to the historical models of Cyprian of Carthage, Ephrem of Syria, and Athanasius of Alexandria, Liddell is an inspiring example of doing meaningful theology in the context of mission and suffering. Finally, what is also remarkable was the pace in which Liddell studied Scripture. He wrote, "Don't read hurriedly . . . every word is precious. Pause, assimilate" (p. 247). With some time on his hands, his approach to the Word was not rushed and he pursued his own sort of lectio divina (divine reading) made famous by the monk Benedict of Nursia and his followers. In short: slow theology in the crucible of hardship and suffering. Comments are closed.

|

Archives

November 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed